The giant goanna

For roughly one hundred and fifty years Varanus priscus went by the name of Megalania prisca, however modern interpretations of this ancient lizard mostly concur that it is actually a species of the current Varanus genus of monitor lizards that we know today. Because it has appeared in many books, websites and television shows under the older name in the past, most people still refer to it as Megalania.

Normally when a genus is absorbed into another to create a new species, the original species epithet is used, but Megalania is a feminine term whereas Varanus is a masculine one. As such instead of becoming Varanus prisca as would usually happen, the species name had to altered to become Varanus priscus instead.

Palaeontologists have been trying to identify the closest living relative of this giant monitor lizard since it was first discovered and similarities between it and living monitor lizards were established even before it was moved into the same family as them.

Today the largest monitor in Australia is the Perentie (Varanus giganteus), but most consider the Lace monitor (Varanus varius) to be a better analogy. Still another contender for similar ecological niche is the Komodo dragon (Varanus komodoensis) that is currently the largest known monitor lizard.

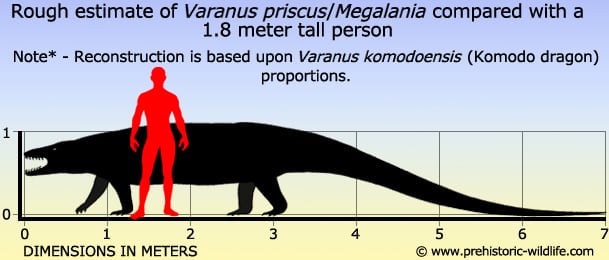

Because Varanus priscus remains are still largely incomplete, reconstructions and size estimates are based upon comparisons to other monitor lizards. Unfortunately not only are there different methods of comparison, different monitors have different body proportions, all things that have resulted in a range of sizes.

Stephen Wroe established in 2002 that this lizard could range between three and half and four and a half meters, but a conflicting study by Ralph Molnar in 2004 propositioned that Varanus priscus (still known as Megalania) could grow between seven and eight meters long.

Molnar’s results depended upon comparison to a Komodo dragon for seven meters, and a Lace monitor for just under eight, although the latter has a proportionately longer tail relative to its body size.

Hunting and position in the ecosystem

The ecosystems of Pleistocene Australia had animals that were very different to the rest of the world thanks mostly to the continents isolation. Here there were a number of large flightless birds that were similar to others that had long gone extinct upon other continents.

One of the largest animal groups were marsupial mammals, already rare in other parts of the world and represented by giant wombats like Diprotodon and Phascolonus, and giant Kangaroos like Procoptodon, all of which would have been valid prey animals for a large meat eater like Varanus priscus.

The mammals would have been especially susceptible to attacks from a large mouthed, sharp, serrated toothed predator which could have done a lot of damage to their soft unarmoured bodies.

However there was also competition for the position of apex predator with other predators including the terrestrial crocodile Quinkana which may have rivalled Varanus priscus in size, and the marsupial lion Thylacoleo.

Varanus priscus was not just a big lizard, it had a very robust construction, especially the skull that could withstand a lot of stress and punishment. We also know that living monitor lizards, especially larger species have very tough scales that have often been described as being similar to chainmail.

Varanus priscus also probably didn’t have to rely upon its mouth to attack animals as others like the Komodo dragon have been observed using their tails to knock prey animals off their feet so that they can’t run away.

One area where Varanus priscus fell short however was running speed, as although monitor lizards are very quick to accelerate, they cannot match dedicated runners in a flat race once they have got up to speed. This means that Varanus priscus would typically have to operate in a very narrow window of opportunity when prey was just close enough to attack without giving it time to escape.

This suggests that its behaviour would be centred on the use of using ambush tactics such as lurking in the undergrowth and staying near game trails and watering holes like other predators do in order to maximise their chances of coming into contact with prey. Of course just like some monitor lizards do today, Varanus priscus may have also actively sought out carrion, or even driven other predators like Thylacoleo from their kills.

The most important sense for monitor lizards is that of smell, and this can be seen in the way that they frequently flick out their tongues. Every time the tongue shoots out it picks up scent particles in the air of its surface which then get tasted by an organ in the snout when the tongue is flicked out.

The tongue is also forked so that when one prong picks up a greater coating of particles than the other the lizard knows which direction to turn in.

The lizard then follows the scent till it finds the source which can be anything from a carcass to a sick or injured animal. In the case of the latter the excellent vision then comes into use, although living monitor lizards seem to be most suited to seeing in daylight conditions. Varanus priscus would have likely displayed this tracking behaviour, but on scale that saw it hunting the other megafauna alive at that time.

Although direct evidence is lacking, Varanus priscus is generally thought to have been able to use venom from glands that would have been in the lower jaw. This is based upon research concerning the Komodo dragon by the University of Melbourne that began in 2005.

Wild Komodo dragons have long been presumed to have a toxic bite from the number of bacteria strains that have been sampled from the saliva of wild specimens that are notably absent from those living in captivity.

It’s possible that this bacteria living in the mouth of wild Komodo dragons is the result of them feeding from carcasses where bacteria such as E. coli are present. CAT Scanning of Komodo dragon heads confirmed the presence of internal organs in the lower jaws that later removal and study revealed to be venom glands.

Venom from these glands that contains agents that prevent the blood from clotting as well as causing other problems such as muscle paralysis passes through pores in the mouth to mix with the saliva. As the Komodo dragons teeth puncture and tear the flesh of their prey, the venom mixes into the wound so that not only does the prey suffer massive blood loss from the damage of the bite, it also has to contend with the effects of the venom on top of that.

It’s still impossible to be absolutely certain if Varanus priscus also had this venom producing ability, but so far it seems that all other members of the Varanus genus alive today also have these venom glands.

By relation to these other species it would actually be unusual if Varanus priscus did not have venom glands, and if it did indeed have them it would possibly be the largest venomous animal ever to have existed. Utilising venom in its hunting would also make it a much more effective predator of the large Australian megafauna from giant wombats like Diprotodon, to possibly even large flightless birds like Genyornis.

Varanus priscus/Megalania prisca in cryptozoology

As far as science is currently concerned Varanus priscus exists only in the fossil record, and died out at around the time of most of the other large Australian megafauna. Despite this there are still occasional sightings of both huge lizards and large animals like cattle that have been completely butchered and torn apart coming from the Australian outback. Reports are also known from nearby New Guinea of similar large monitor lizards.

Critics of these stories often point out a number of theories as to why it is impossible for giant monitor lizards to still be alive. One is that Australia today has a far more arid climate than what it had during the Pleistocene, and that the large mammals that Varanus Priscus preyed upon are no longer present.

Some critics also claim that people who claim to have seen giant monitor lizards are simply misinterpreting animals like crocodiles or even inanimate objects such as logs. Critics often also accuse witnesses of making the story up, although grounds for this accusation must always be established on a case by case basis.

One of the most popular theories against large monitor lizards being alive is that they are so huge it should be impossible for them to hide. Another is that it takes a population of several individuals for a species to survive which means that not just one but several giant lizards should be being seen.

These are all valid points that should be seriously considered, however there is another set of theories that counter these ideas.

First is that while most of Australia is arid grassland and desert, there are extensive areas of lush forest and swamps that cover areas that are larger than some small countries.

With most of the Australian population living in built up areas of relatively small size, these outback areas are not often explored, and parts remain unknown to this day.

Also when people describe the creature that they see they usually use the term ‘goanna’ (in Australia monitor lizards are more commonly called goannas) and not only insist that they are seeing a goanna and not a croc, but that the lizard was moving.

Animals that could support a large monitor lizard also exist in the form of kangaroos, buffalo, and domestically sourced animals like cattle and horses.

Perhaps most frightening of all these possibilities is the observation of how females of the related Komodo dragon that have not had any contact with males, still lay eggs that are fertile enough for a young komodo dragon to hatch out.

Assuming Varanus priscus as a very closely related animal had the ability to lay eggs by parthenogenesis (without sexual reproduction), this species would not need a large population to survive, just a few females.

This is something that could also be key to their survival since large predatory animals do not normally have large populations as to avoid exhausting the available prey in an ecosystem.

Additionally wild monitor lizards known to exist, including the large Perentie (Varanus giganteus) usually exhibit shy behaviour around humans, often retreating when they detect them.

Despite all this there is still currently no direct evidence for the continued existence of Varanus priscus, and without a body or exceptionally conclusive video or photographic evidence it will continue to be regarded as an extinct reptile.

But as the saying goes, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and many of the creatures we know today were once regarded as not possibly being real. One of the best examples of this is that of the gorilla, an animal that was once considered by science to be a mythical creature that only existed in African folklore until one was actually shot and documented.

The potential for the existence for large monitor lizards in Australia exists, but this does not necessarily mean that they are surviving examples of Varanus priscus.

Further Reading

- – Description of Some Remains of a Gigantic Land-Lizard (Megalania Prisca, Owen) from Australia – Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London – Richard Owen – 1859.

- – The morphology and relationships of the largest known terrestrial lizard, Megalania prisca Owen, from the Pleistocene of Australia. – Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 87: 239–250. – M. Hecht – 1975.

- – Rebuilding a giant lizard. – In Clayton, Georgina; Archer, Michael. Vertebrate zoogeography & evolution in Australasia: (animals in space and time). Carlisle, W.A.: Hesperian Press – T. Rich & B. Hall – 1984.

- – Possible affinities between Varanus giganteus and Megalania prisca. – Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 39: 232. – M. S. Y. Lee – 1996.

- – A review of terrestrial mammalian and reptilian carnivore ecology in Australian fossil faunas, and factors influencing their diversity: the myth of reptilian domination and its broader ramifications. – Australian Journal of Zoology 50: 1–24. – S. Wroe – 2002.

- – Megafaunal extinction in the late Quaternary and the global overkill hypothesis – Alcheringa 28: 291–33 – S. Wroe, J. Field, R. Fullagar & L. S. Jermiin – 2004.

- – Neurocranial osteology and systematic relationships of Varanus (Megalania) prisca Owen, 1859 (Squamata: Varanidae). – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 155: 445–457. – J. J. Head, P. M. Barret & E. J. Rayfield – 2009.

- – A central role for venom in predation by Varanus komodoensis (Komodo Dragon) and the extinct giant Varanus (Megalania) priscus – PNAS 106 (22): 8969–74. – Bryan G. Fry, Stephen Wroe, Wouter Teeuwisse, Matthias J. P. van Osch, Karen Moreno, Janette Ingle, Colin McHenry, Toni Ferrara, Phillip Clausen, Holger Scheib, Kelly L. Winter, Laura Greismana, Kim Roelants, Louise van der Weerd, Christofer J. Clemente, Eleni Giannakis, Wayne C. Hodgson, Sonja Luz, Paolo Martelli, Karthiyani Krishnasamy, Elazar Kochva, Hang Fai Kwok, Denis Scanlon, John Karas, Diane M. Citron, Ellie J. C. Goldstein, Judith E. Mcnaughtan & Janette A. Norman – 2009.

- – Temporal overlap of humans and giant lizards (Varanidae; Squamata) in Pleistocene Australia. – Quaternary Science Reviews. 125: 98–105. – Gilbert J. Price, Julien Louys, Jonathan Cramb, Yue-xing Feng, Jian-xin Zhao, Scott A. Hocknull, Gregory E. Webb, Ai Duc Nguyen & Renaud Joannes-Boyau – 2015.