In Depth

Hallucigenia was first identified as the Cambrian aquatic worm Canadia by Charles Doolittle Walcott in 1911. However a study of the Canadia fossils by Simon Conway Morris in 1977 brought to light the discovery that the fossils did not represent the same creature. Because of its bizarre appearance of spikes and tentacles, Conway Morris gave the different individuals the name Hallucigenia because of their ‘bizarre and dream-like quality’. However this realisation would be but the beginning of even more confusion about how it Hallucigenia lived.

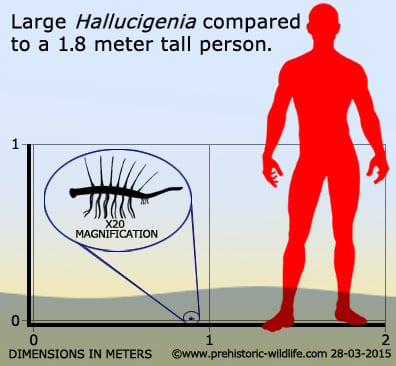

Fossils of Hallucigenia appear worm like with seven spines on one side, and seven pincer tipped tentacles on the other. Six of the tentacles match the spines for placement, the seventh however is forward. There are also three much smaller tentacles further along. On the ends of the main body were a blob on one end and a flexible tube on the other. Such a creature would be enough to make many palaeontologists give up and quit, but Morris persevered and worked out a conceivable reconstruction of the living creature. The first and original interpretation of Hallucigenia had it using its spines for walking. The flexible tail would reach down to the sea bottom and picking up morsels of food. The tail would then curl up and pass the morsel onto the first tentacle which would then pass it on to the next. The food morsel would then travel down the line of tentacles towards the ‘blob’ that was interpreted as being the head.

There are a few problems with this interpretaion the first of which is that spikes, while possibly used for walking, would have been quite cumbersome. The second is that this method requires a lot of physical effort for feeding upon food sources that are possibly low in nutrients. Usually animals put as short a distance as possible between their mouths and their food source but in this reconstruction the distance is at its potential maximum. The third problem is that this method does not explain either the presence or function of the smaller tentacles at the base of the tail.

A possible alternative to the above is if the spines were indeed placed at the bottom, could be that the spines were used to anchor Hallucigenia amongst rocks in the path of oceanic, or tidal currents. The tentacles would then drift upwards with their pincers catching food particles that were drifting in the current. The tentacles could then pass the food onto the mouth whichever end that may be, but if the mouth was on the tail and not the blob, then the tail could arc around to pick up the food morsels from the tentacles. Such a method would essentially see Hallucigenia living like a portable sea anemone.

The second interpretation of Hallucigenia, and this is the one that is general accepted today, is to flip Hallucigenia over so that the spines point upwards and the tentacles are used for walking. This interpretation was proposed by Lars Ramskold and Hou Xianguang in 1991, and is based upon fossils recovered from the Maotianshan shales of China. Not only does this see the spines in a defensive position, the tentacles are usually reconstructed to be in pairs. The blob was also interpreted as a stain caused by preservation, the claim based upon the observation that it is not present in all specimens.

Although this is the most often represented reconstruction today, paired tentacles are not currently known in Hallucigenia fossils. The spines are also not considered by all to have been hard structures because they are never found on their own like the hard parts of other soft bodied creatures. The fossilised arrangement of the spines also only covers the main body. While this could theoretically deter suction feeders, other predators would have had quite a simple time avoiding them.

The phylogenetic position of Hallucigenia is also strongly debated, and while many entries of Hallucigenia place within the Onychophora (velvet worms), not everyone is convinced that Hallucigenia belongs here. The possibility has even been raised that Hallucigenia may in fact be part of a larger animal, like how another Cambrian creature called Anomalocaris was first identified as a small shrimp until other body parts were pieced together to form the actual animal. There also what appears to be robust and gracile morphs of Hallucigenia which in 2002 were interpreted by Desmond Collins to represent male and female individuals.

Further Reading

– A new metazoan from the Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia. – Palaeontology 20: 623–640. – S. Comway Morris – 1977. – The second leg row of Hallucigenia discovered. – Lethaia 25 (2): 221–4. – Lars – Ramsk�ld – 1992. – A new species of Hallucigenia from the Cambrian Stage 4 Wulongqing Formation of Yunnan (South China) and the structure of sclerites in lobopodians. – Bulletin of Geosciences 87: 107–124. – M. Steiner, S. Hu, J. Liu & H. Keupp – 2012. – Beyond the Burgess Shale: Cambrian microfossils track the rise and fall of hallucigeniid lobopodians. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1767): 20131613. – Jean-Bernard Caron, Martin R. Smith & Thomas H. P. Harvey – 2013. – Hallucigenia’s onychophoran-like claws and the case for Tactopoda. – Nature. 514 (7522): 363–366. – M. R. Smith & J. Ortega-Hern�ndez – 2014. – Hallucigenia’s head and the pharyngeal armature of early ecdysozoans. – Nature. 523 (7558): 75–78. – Martin R. Smith & Jean-Bernard Caron – 2015. – A hypothetical reconstruction of Hallucigenia. – PeerJ Preprints. 7: e27551v1 (1–10). – Christian McCall – 2019.