In Depth

The first remains of Albertosaurus were recovered from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation in 1884, and these were the type specimen along with a smaller skull and some of the post crania. However Albertosaurus was not yet identified and when these parts were studied in 1892 by Edward Drinker Cope, he assigned them to another dinosaur called Laelaps incrassatus that he had named earlier in 1866. Now this is where things start to get confusing because the name Laelaps had already been applied to a mite, and because of this Othniel Charles Marsh had changed Laelaps to Dryptosaurus in 1877. Anyone who recognises the names Marsh and Cope is probably already familiar with the ‘Bone Wars’ and the fierce rivalry between them. Cope refused to acknowledge the change and it was up to the eminent palaeontologist Lawrence Lambe to formally rename the specimens Dryptosaurus incrassatus. This still was not the end because the palaeontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn disputed the renaming citing two key reasons. The first was that Dyptosaurus incrassatus (formerly Laelaps incrassatus) was based only upon the description of generic tyrannosaur teeth with no bone material to back it up, thus making accurate comparison near impossible. The second was that the fossil material recovered was different enough from the Dryptosaurus type species D. aquilunguis to be considered its own species. So in 1905, Osborn renamed the material Albertosaurus in reference to the part of the world it was found.

Today we know enough about Albertosaurus to be certain it deserves its own genus, but there is now another bit of contention associated with it. Some palaeontologists have claimed that another tyrannosaur named Gorgosaurus is actually a species of Albertosaurus. Both are members of the tyrannosauridae group and both have a similar morphology, being more gracile than other members such as Tyrannosaurus and Daspletosaurus. On the other hand, some palaeontologists claim that while they are similar, there are enough differences between them to distinguish the two and thus keep them separate. This debate is still on going and is not likely to be settled until further study or new fossil material can point towards which is more correct. Like the other tyrannosaurids, Albertosaurus had conical ‘banana teeth’. Although not suitable for slicing flesh, they could crunch though bone and rip flesh from a carcass. In Albertosaurus the teeth seem to have crack like serration in a similar fashion found in the teeth of the ancient pelycosaur Dimetrodon. One thing that Albertosaurus has, that Dimetrodon did not, is the presence of ampulla at the base of the crack. This is a round void that displaces stress forces placed on the teeth when Albertosaurus bit into something, significantly increasing their resilience. Albertosaurus also had more teeth than the larger members of the tyrannosaurids with over sixty in its mouth.

There is some evidence to suggest that Albertosaurus may have actually been a pack hunter. The palaeontologist Barnum Brown had discovered a bone bed containing multiple tyrannosaur remains in 1910. Brown did not have time to excavate the site properly and so took what he could, but after this the site was forgotten and lost. It was not until 1997 when a team led by Dr Philip J. Currie rediscovered the bed, that its significance was realised to modern day science.

There are enough remains in what is now called the Dry Island bone bed to identify twenty-two individuals of all different ages and sizes. Not all are convinced about the pack theory stating that they may have been drawn together by ecological factors such as a drought forcing them around a watering hole. Others have stated they may have been killed by their own kind in competition for feeding rights at a carcass. What has to be remembered here is that only Albertosaurus remains were found, and the individuals were of different ages. Pack hunting animals today also form groups of just one species, with individuals of different ages represented in the same group. Regardless of whether Albertosaurus did or did not hunt in packs, the fossil material recovered from the Dry Island bone bed has allowed palaeontologists to study the way Albertosaurus and by extension other tyrannosaurids may have grown. In fact Albertosaurus is now the best known of the tyrannosaurids.

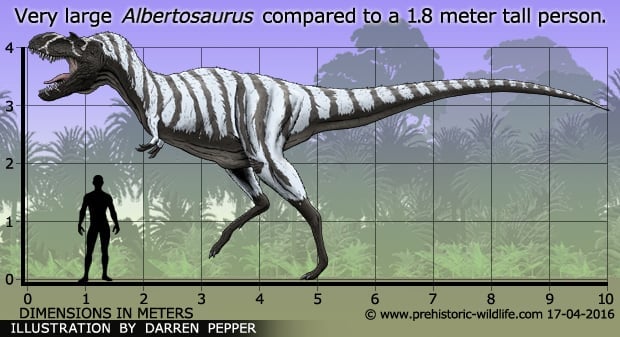

It is thought that Albertosaurus would have grown steadily for the first few years of its life before undergoing a massive growth spurt until reaching sexual maturity. Once this happens, growth slows down to a much slower rate until the individual reaches its maximum potential size or it dies from some other means. It’s possible that the stresses exerted upon the body by such rapid growth may actually cause the body to ‘burn out’ and become more susceptible to disease or other ailments in all but the healthiest of individuals. This would explain the large number of adult Albertosaurus specimens recovered that had not yet reached their maximum potential size, with most approaching nine meters in length as opposed to the maximum recorded ten.

Further Reading

– Tyrannosaurus and other Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaurs. – Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 21(14):259-265. – H. F. Osborn – 1905. – Albertosaurus arctunguis, a new species of therapodous dinosaur from the Edmonton Formation of Alberta. – University of Toronto Studies, Geological Series 25: 1–42. – William A. Parkes – 1928. – Tyrannosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of western Canada. – National Museum of Natural Sciences Publications in Paleontology 1: 1–34. – Dale A. Russel – 1970. – Possible evidence of gregarious behaviour in tyrannosaurids. – Gaia 15: 271–277. – Philip. J. Currie – 1998. – A kerf-and-drill model of tyrannosaur tooth serrations, by W. L. Abler. In, Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, Indiana University Press. – D. H. Tanke, K. Carpenter & M. W. Skrepnick – 2001. – Allometric growth in tyrannosaurids (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of North America and Asia. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40 (4): 651–665. – Philip. J. Currie – 2003. – Cranial anatomy of tyrannosaurids from the Late Cretaceous of Alberta. – Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48 (2): 191–226. – Philip. J. Currie – 2003. – Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid phylogeny. – Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 48 (2): 227–234. – Philip J. Currie, J�rn H. Hurum & Karol Sabath – 2003. – Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs. – Nature 430 (7001): 772–775. – Gregory M. Erickson, Peter Makovicky, Philip. J. Currie, Mark A. Norell, Scott A. Yerby & Christopher A. Brochu – 2004. – An unusual multi-individual tyrannosaurid bonebed in the Two Medicine Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) of Montana (USA), by Philip J. Currie, David Trexler, Eva B. Koppelhus, Kelly Wicks & Nate Murphy – 2005. – Tyrannosaur life tables: an example of nonavian dinosaur population biology. – Science 313 (5784): 213–217. – Gregory M. Erickson, Philip. J. Currie, Brian D. Inouye & Alice A. Wynn – 2006. – The heterodonty of Albertosaurus sarcophagus and Tyrannosaurus rex: biomechanical implications inferred through 3-D models. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1253–1261. – Miriam Reichel – 2010. – On gregarious behavior in Albertosaurus. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1277–1289. – Philip J. Currie & David A. Eberth – 2010. – Palaeopathological changes in a population of Albertosaurus sarcophagus from the Upper Cretaceous Horseshoe Canyon Formation of Alberta, Canada. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1263–1268. – Phil R. Bell – 2010. – Faunal assemblages from the upper Horseshoe Canyon Formation, an early Maastrichtian cool-climate assemblage from Alberta, with special reference to the Albertosaurus sarcophagus bonebed. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1159–1181. – Derek W. Larson, Donald B. Brinkman & Phil R. Bell – 2010. – A history of Albertosaurus discoveries in Alberta, Canada. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1197–1211. – Darren H. Tanke & Philip J. Currie – 2010. – Quantifying tooth variation within a single population of Albertosaurus sarcophagus (Theropoda: Tyrannosauridae) and implications for identifying isolated teeth of tyrannosaurids. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1227–1251. – Lisa G. Buckley, Derek W. Larson, Miriam Reichel & Tanya Samman – 2010. – A revised life table and survivorship curve for Albertosaurus sarcophagus based on the Dry Island mass death assemblage. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1269–1275. – Gregory M. Erickson, Philip J. Currie, Brian D. Inouye & Alice A Winn – 2010. – A taxonomic assessment of the type series of Albertosaurus sarcophagus and the identity of Tyrannosauridae (Dinosauria, Coelurosauria) in the Albertosaurus bonebed from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Campanian–Maastrichtian, Late Cretaceous. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1213–1226. – Thomas D. Carr – 2010. – Stratigraphy, sedimentology, and taphonomy of the Albertosaurus bonebed (upper Horseshoe Canyon Formation; Maastrichtian), southern Alberta, Canada. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 47: 1119–1143. – David A. Eberth & Philip J. Currie 2010.