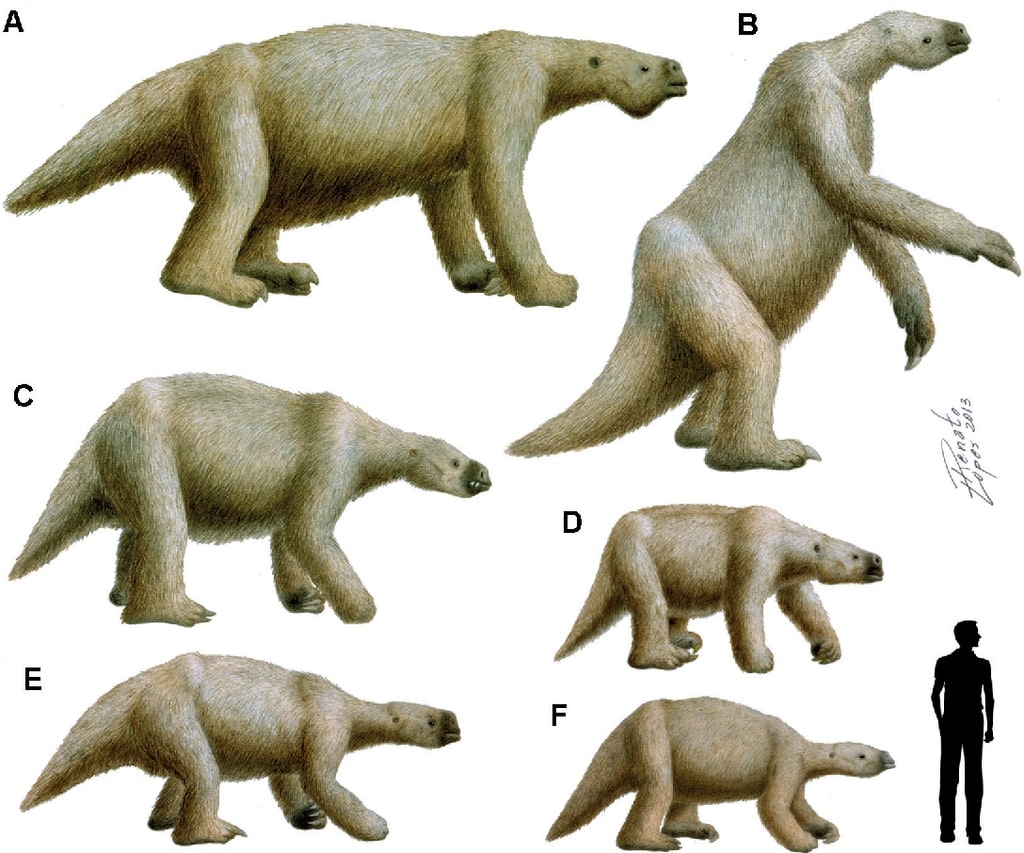

When you think of sloths, you probably picture small, slow creatures hanging from tree branches.

But prehistoric sloths, especially the giant ground sloths of the Ice Age, were nothing like their modern relatives.

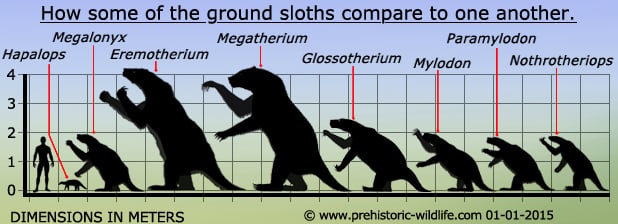

Some species grew as large as elephants and roamed across the Americas for millions of years.

Then, about 11,000 years ago, these ancient giants mysteriously vanished — leaving behind fossils and questions scientists are still trying to answer.

During the Ice Age, these massive plant-eaters shaped entire landscapes.

Some stood 20 feet tall when they reared up on their hind legs. Others dug enormous burrows that still exist today.

From Alaska to Argentina, ground sloths were among the most successful animals of their time.

Let’s explore ten incredible species that once ruled the prehistoric world.

#1 Megatherium americanum

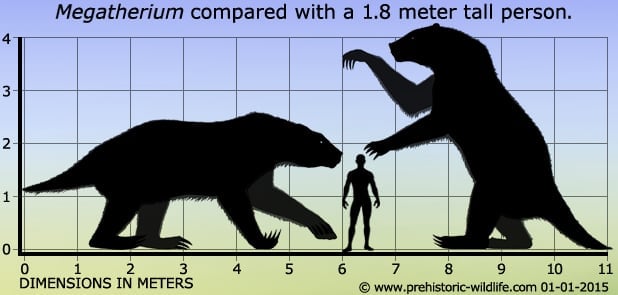

Megatherium americanum was the heavyweight champion of prehistoric sloths. This massive animal weighed up to 4 tons – about as much as an African elephant.

From nose to tail, it stretched 20 feet long. When it stood on its hind legs to feed, it could reach leaves 20 feet off the ground.

Scientists have found many Megatherium fossils in South America, especially in Argentina and Brazil.

These bones tell us the giant lived from about 5 million years ago until just 11,000 years ago.

Its name means “great beast,” and it certainly lived up to that title.

How Did Something So Big Find Enough Food?

Megatherium had some clever adaptations for finding food.

- Its huge claws, which could grow 20 inches long, weren’t for hunting – they were perfect tools for pulling down branches.

- The sloth would rear up on its hind legs, using its thick tail as a tripod for balance, then hook branches with those massive claws.

- This giant needed about 660 pounds of plants every day.

- Its constantly growing teeth never wore out, even from chewing tough, fibrous plants.

- Scientists studying fossilized dung found that Megatherium ate everything from soft leaves to hard, woody plants.

Think of it as nature’s largest vegetarian, spending most of its day eating to fuel that enormous body.

#2 Eremotherium laurillardi

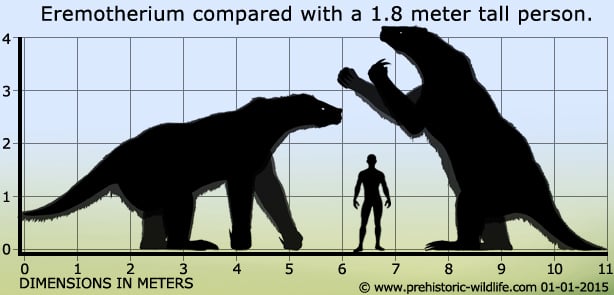

Eremotherium laurillardi was almost as large as Megatherium, weighing about 3 tons.

What makes this sloth special is its incredible journey.

It started in South America but migrated north when the continents connected about 2.5 million years ago.

Fossils have been found from Brazil all the way to South Carolina.

This prehistoric giant preferred warm, coastal areas.

Many fossils come from ancient swamps and river valleys in Florida and Georgia.

Unlike some ground sloths that lived in mountains or deserts, Eremotherium stuck to lowlands where the climate was mild and plants were plentiful.

Built for Warm Weather

While similar in size to Megatherium, Eremotherium had a narrower head and longer snout.

These differences meant it probably ate different plants.

Its teeth were better suited for softer leaves and fruits found in warmer climates.

Fossilized footprints in New Mexico show something fascinating – Eremotherium walked with its feet turned inward.

This awkward-looking walk actually helped distribute its massive weight, keeping those giant claws from scraping the ground with every step.

#3 Megalonyx jeffersonii

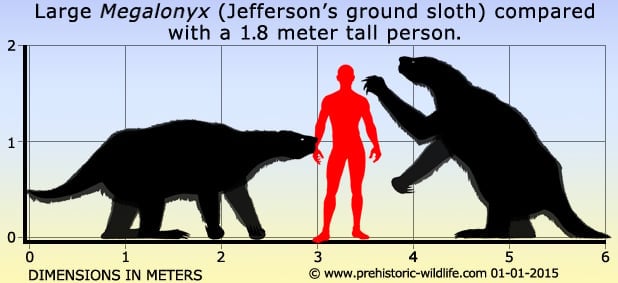

This ground sloth has a unique claim to fame – Thomas Jefferson himself studied its fossils in 1797.

Jefferson thought he’d found bones from a giant lion, but he’d actually discovered North America’s first scientifically described ground sloth. Scientists later named it Megalonyx jeffersonii in his honor.

Megalonyx was smaller than the South American giants, weighing about 2,200 pounds (roughly the size of a modern ox).

But what it lacked in size, it made up for in range.

This adaptable sloth lived everywhere from Alaska to Mexico over its 9-million-year existence.

Surviving the Cold

Unlike its tropical cousins, Megalonyx thrived in cold climates.

Scientists have found fur impressions with some fossils, suggesting these sloths had thick, warm coats.

Their sturdy build and shorter limbs helped them conserve heat during ice ages.

Cave deposits often contain Megalonyx fossils, and some caves even preserve claw marks on the walls.

These scratches match the three-clawed hands of this species perfectly.

Imagine a creature the size of an ox using caves for shelter during harsh winters – it’s like finding an ancient apartment building with the tenants’ scratch marks still visible.

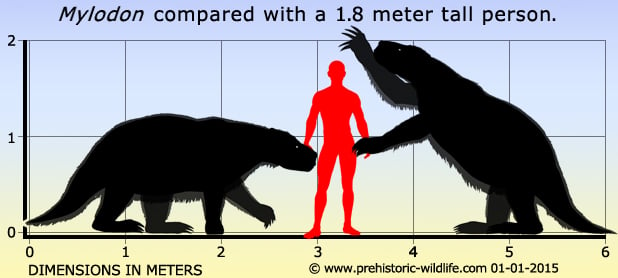

#4 Mylodon darwinii

Charles Darwin discovered this sloth’s fossils during his famous voyage on the HMS Beagle.

Mylodon darwinii was a medium-sized ground sloth, weighing between 2,200 and 4,400 pounds.

It lived in the grasslands of Argentina and Chile from about 1.8 million to 10,000 years ago.

The most amazing Mylodon discovery came from a cave in Chile called Cueva del Milodón.

Here, the cold, dry conditions preserved not just bones but also skin, fur, and even dung. This incredible preservation gives us a complete picture of what these extinct animals really looked like.

Nature’s Tank

Mylodon had a secret weapon – built-in armor.

Small bones called dermal ossicles were embedded in its skin, creating a flexible chainmail beneath its fur.

Each piece was about the size of a pebble, and hundreds of them worked together to protect the sloth from predator attacks.

Scientists studying preserved dung learned that Mylodon ate grasses, leaves, and herbs.

They also found sand and grit in the dung, suggesting these sloths sometimes ate soil.

Modern animals do this to get minerals or help with digestion, and Mylodon probably did the same.

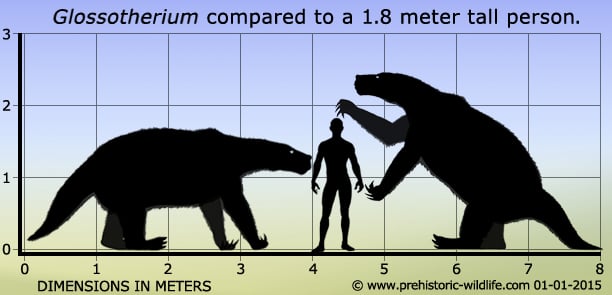

#5 Glossotherium robustum

Glossotherium robustum weighed about 3,300 pounds and had incredibly powerful front limbs.

Recently, scientists in Brazil and Argentina discovered massive tunnels called palaeoburrows.

Some stretch over 300 feet long with chambers 6 feet high. The claw marks on the walls match Glossotherium perfectly.

These are the largest burrows ever made by any animal. Imagine a creature the size of a small car digging tunnels you could walk through standing up.

These burrows probably provided shelter from weather and predators, and maybe even served as nurseries for raising young.

Evidence of Family Life

The complexity of these burrows suggests Glossotherium wasn’t a loner.

Multiple chambers and connecting tunnels hint at family groups living together.

Some burrows contain fossils from several individuals of different ages, supporting the idea that these sloths had social lives.

This behavior makes sense when you consider the effort needed to dig such massive tunnels.

Working together would make the job easier, and sharing the space would provide safety in numbers against predators like saber-toothed cats.

#6 Lestodon armatus

Lestodon armatus was another South American giant, weighing up to 7,500 pounds.

This massive sloth specialized in eating grass – not the soft lawn grass we know today, but tough, sharp-edged grasses that would wear down most animals’ teeth quickly.

Lestodon solved this problem with continuously growing teeth that never wore out completely.

Its powerful jaws and flat grinding teeth could process plants that other animals couldn’t eat.

This gave it a huge advantage in the vast grasslands of ancient Argentina.

Living in Herds

Fossil sites containing many Lestodon individuals suggest these giants may have lived in groups.

Finding multiple animals of different ages together indicates family groups or herds.

This social behavior would have provided protection against predators.

Living in groups also makes sense for grass-eaters.

Grasslands can support many herbivores in the same area, unlike forests where food is more spread out.

By tolerating each other’s company, Lestodon herds could watch for danger while feeding.

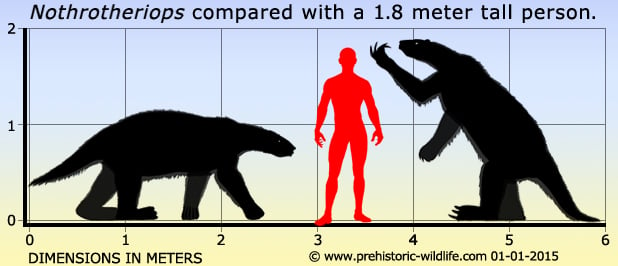

#7 Nothrotheriops shastensis

The Shasta ground sloth was smaller than its giant cousins, weighing only 550-880 pounds.

But Nothrotheriops shastensis was incredibly successful, living throughout the southwestern United States for 1.5 million years.

Its smaller size actually helped it survive in harsh desert environments where food was scarce.

Dry caves in Arizona and Nevada have preserved this sloth’s remains perfectly.

Scientists have found complete skeletons, mummified skin, and thousands of fossilized dung pellets.

This treasure trove of evidence tells us more about this sloth’s daily life than we know about most prehistoric animals.

Desert Menu

Analysis of fossilized dung shows Nothrotheriops ate an amazingly varied diet – over 70 different plant species.

It enjoyed Joshua trees, agaves, and even cacti. During wet seasons, it ate more grass.

During droughts, it switched to water-storing plants like cacti.

This dietary flexibility was key to survival in the desert.

By eating whatever was available, Nothrotheriops thrived where pickier eaters would have starved. It even helped its environment by spreading seeds through its dung, planting the next generation of desert plants.

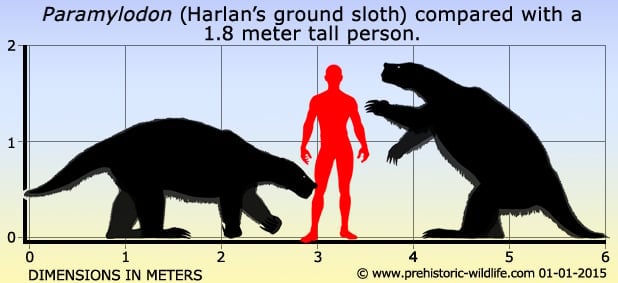

#8 Paramylodon harlani

Paramylodon harlani is famous from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, where hundreds of individuals got stuck in natural asphalt over thousands of years.

This medium-sized sloth weighed 2,200-3,300 pounds and lived across western North America.

The tar pits preserved these sloths incredibly well. Scientists have found not just bones but evidence of fur, skin, and even parasites.

This preservation is like a time capsule, showing us details about the sloth’s health, diet, and daily life that would normally be lost forever.

Paramylodon’s A Love of Water

Chemical analysis of Paramylodon bones reveals something surprising – these sloths spent lots of time near water.

They probably fed on water plants, using their strong claws to dig up roots from muddy riverbanks and marshes.

Many Paramylodon fossils show signs of arthritis, especially in the spine and leg joints.

This tells us these animals regularly stood upright, putting stress on their bodies.

Like other ground sloths, they probably stood on their hind legs to reach food, despite the wear and tear on their joints.

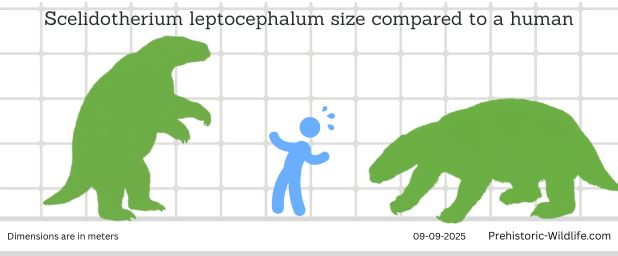

#9 Scelidotherium leptocephalum

Scelidotherium leptocephalum had one of the most unusual skulls among ground sloths.

Its long, narrow head housed an extra-large nose cavity, possibly giving it an excellent sense of smell.

This medium-sized sloth weighed about 1,760-2,200 pounds.

Fossils found across Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil show this sloth preferred areas where grasslands met forests.

It lived successfully in these mixed habitats for about 3 million years, from the Pliocene through the end of the Ice Age.

Selective Feeding

While some sloths ate whatever plants they could find, Scelidotherium was choosy.

Microscopic scratches on its teeth show it carefully selected specific plant parts, probably picking the most nutritious leaves and shoots while avoiding tougher stems.

This picky eating strategy worked well. By targeting high-quality food, Scelidotherium could maintain a smaller body size while still getting enough nutrition.

It’s like choosing to eat just the hearts of artichokes instead of the whole thing – more work, but higher reward.

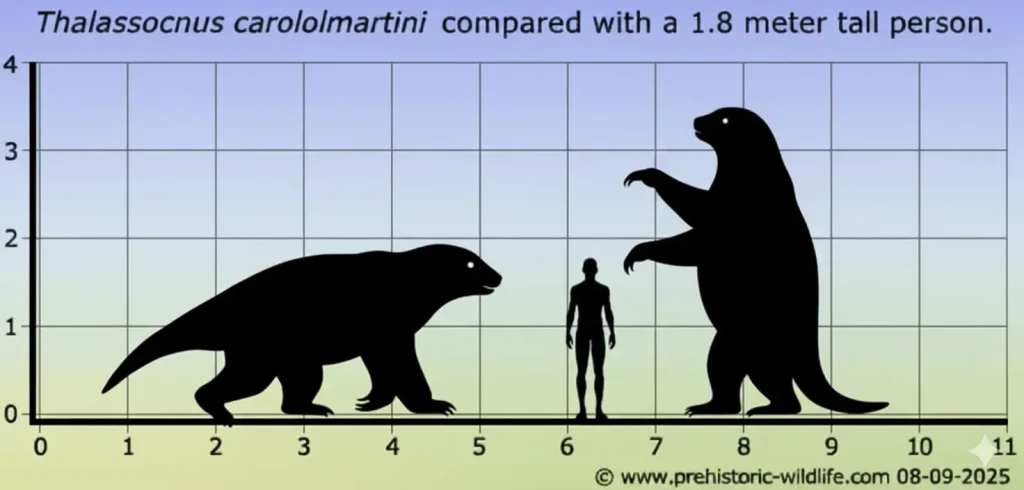

#10 Thalassocnus

Thalassocnus breaks all the rules for what we expect from a sloth.

Over 5 million years, this genus evolved from land-dwelling animals into semi-aquatic swimmers along the coasts of Peru and Chile.

Five different species show gradual changes toward ocean life.

The earliest species weighed about 265 pounds and showed small adaptations for water.

Later species developed heavy, dense bones that acted like built-in diving weights.

Their tails became powerful swimming organs, and their snouts grew longer for feeding underwater.

From Land to Sea

The fossil record of Thalassocnus is like watching a slow-motion movie of evolution. Each species shows more aquatic features:

- Bones became denser to help them sink and walk on the seafloor

- Arm and leg bones grew longer for better swimming strokes

- Tail bones changed shape to work like a beaver’s paddle

- Teeth adapted for eating seaweed instead of land plants

These sloths probably fed like modern marine iguanas, diving down to munch on seaweed and kelp in shallow coastal waters.

No other sloth lineage ever attempted such a dramatic lifestyle change.

Conclusion

The story of prehistoric sloths shows us how incredibly adaptable life can be. These amazing animals conquered every environment from frozen tundra to tropical beaches to ocean waters. For over 30 million years, they were among the most successful mammals on Earth.

Their extinction removed crucial players from American ecosystems. These giant herbivores shaped plant communities, dispersed seeds, and even changed the landscape with their burrows. Modern ecosystems still show the effects of their absence.

Frequently Asked Questions

How big was the largest prehistoric sloth?

The largest prehistoric sloth, Megatherium americanum, reached 20 feet long and weighed up to 4 tons – about the same as an African elephant. When standing upright, it could reach vegetation 20 feet high, making it one of the tallest animals of its time.

When did giant ground sloths go extinct?

Most giant ground sloths disappeared about 10,000-11,000 years ago at the end of the Ice Age. This timing matches both climate change and human arrival in the Americas. Some smaller species on Caribbean islands may have survived until about 4,000 years ago.

What did prehistoric sloths eat?

All prehistoric sloths were plant-eaters with varied diets. They consumed leaves, fruits, grasses, and even tough desert plants like cacti. Some were generalists eating whatever they found, while others specialized in specific plants. Their diet depended on their habitat and body size.

Could giant ground sloths climb trees?

No, giant ground sloths were far too large and heavy for tree climbing. Unlike modern tree sloths, they lived entirely on the ground. They could stand upright to reach high branches but couldn’t climb. Their massive size and ground-adapted bodies made tree-dwelling impossible.

Were prehistoric sloths dangerous to humans?

Prehistoric sloths were peaceful plant-eaters that probably avoided confrontation. However, their size and huge claws made them formidable if threatened. Like modern herbivores such as hippos or buffalo, they were likely dangerous only when defending themselves or their young.

Why were prehistoric sloths so much bigger than modern sloths?

Ground-dwelling allowed prehistoric sloths to grow much larger than tree-dwelling species. Large size helped them defend against predators, reach more food sources, and digest tough plants more efficiently. Modern sloths stayed small to live in trees where large animals can’t survive.

Where can I see prehistoric sloth fossils?

Many natural history museums display ground sloth fossils. Famous locations include the La Brea Tar Pits Museum in Los Angeles, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and the Natural History Museum in London. Regional museums in areas where fossils were found often have excellent local specimens.

Did prehistoric sloths live with dinosaurs?

No, prehistoric sloths never met dinosaurs. Dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago, while the earliest sloths appeared about 35 million years ago. Ground sloths did live alongside other ice age giants like mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and giant armadillos.