Large flightless birds are well known in the fossil records of the world’s southern continents, but it is usually the ‘terror birds’ of the Phorusrhacidae that usually steal the thunder of the others. Titanis manages to stand out from these other terror birds, not because it was one of the largest or most terrifying, but because it was the first and so far only one known in North America. It is thought that Titanis appeared in North America as a result of the Great American Interchange, an event that happened as a result of the creation of the Isthmus of Panama. Further support for this theory comes from the presence of other typically South American animals such as giant ground sloths like Megalonyx being found in North America. It also allowed North American animals such as the sabre toothed cat Smilodon to enter South America.

Titanis the bird

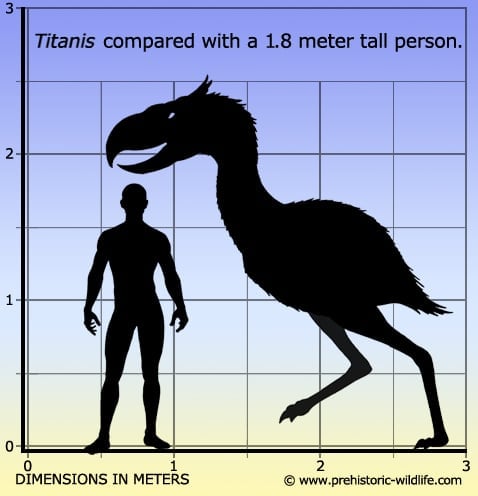

Because only fragmentary remains of the post cranial skeleton are known, much of what we ‘know’ about Titanis has been the result of comparison to other better known and preserved phorusrhacids. This is especially true for the skull which to date (Dec 2011) remains unknown to science. How this comparison works is Titanis fossils are measured and compared to other more complete remains which then allows the missing gaps to be filled in. These more complete reconstructions are then assembled to get a better idea of the complete bird, which in the case of Titanis resulted in a two and a half meter tall terror bird.

Titanis has a strong similarity with other large members of the Phorusrhacidae which has made the reconstruction much easier. However this same similarity has also raised the question of if Titanis actually deserves to be classed as its own genus, something that is very hard to establish with certainty due to the fragmentary nature of original remains. The main synonym contender is the similarly sized Phorusrhacos, the first of the terror birds to be named and discovered. Both are so similar to one another that they both qualify as members of the Phorusrhacinae. However, Titanis lived during a much later time than Phorusrhacos, and the fragmentary remains of Titanis actually do point to a much more robust, heavily built bird. These differences themselves are enough to convince most palaeontologists that Titanis represents a specific genus.

Many entries regarding Titanis mention that it had grasping hands similar to Theropod dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus. This is based upon research by R. M. Chandler, who in 1994 described the construction and orientation of the arms which may have resulted in a clawed fingered hand in a more complete specimen. However this wing structure can actually be seen today in the South American seriema birds which do not have clawed hands. In fact seriema birds are thought to be the closest living relatives to the extinct phorusrhacid terror birds, which is why they often get used as living analogies to the terror birds. Today most researchers discount the idea of clawed hands on Titanis as highly unlikely.

When did Titanis live, and how did its ancestors reach North America?

Estimating the temporal range of Titanis was initially difficult to ascertain because the first fossils were found in Florida’s Santa Fe River. Aside from the fact that divers had to be used to recover the fossils, the fragments would have been washed down from their original locations and were also mixed up with the fragments of other animals. Some of these animals were known from the end of the Pleistocene and because Titanis was found in association to them, some reports erroneously placed Titanis at the end of the Pleistocene as well, some even going so far as to suggest it came into conflict with early human settlers.

A 2006 study undertaken by B. McFadden, J. Labs-Hochstein, R. C. Hulbert and J. A. Baskin Jr. took a much more scientific approach to estimating the real age of Titanis. Usually fossils are age estimated by the level of stratum that they are recovered from. This basically means that the strata is studied and dated, and the fossils dated by location, something that was made impossible by the river washing the Titanis fossils from the original location. Different strata however do have differing levels of minerals which in turn are absorbed by the fossils lying within them. By analysing the mineral content of fossils from known locations where the date has already been established, the team was able to build up a collection of comparative data which allowed for the identification of a fossils temporal place in the fossil record based upon its mineral content.

When the mineral content of the Titanis fragments was established, they were found to most closely match fossils that were created around two million years ago, placing the fragments within the second half of the Gelasian stage of the Pleistocene. Titanis remains from Texas however have been found to be around five million years old, giving Titanis a full temporal range of at least three million years. This also suggests that Titanis was one of the first animals to take part in the Great American Interchange when North and South America became connected. Titanis may have even had an early start by a process of ‘island hopping’ as land masses between the two continents changed in connection to fluxuating sea levels as well as tectonic and volcanic activity that would ultimately lead to the establishment of a permanent land bridge.

Titanis hunting

Aside from looking similar, Titanis probably had similar hunting behaviour to other phorusrhacids. Titanis itself would probably have been a visually orientated predator, relying upon eyesight for everything from prey identification to gauging distances between itself and prey. Analysis of the brain area of the skull in other phorusrhacids has revealed an underdeveloped sense of smell, and while it is not yet possible to know this for certain with Titanis, it is probably likely that as a member of the group, Titanis would also have had limited olfactory ability. This suggests that Titanis was more actively involved in predation than scavenging carcasses, although it does not mean that Titanis never scavenged as most carnivorous animals do when the opportunity presents itself.

Titanis was probably able to match almost any other animal in its ecosystem for speed. While more robust in build than other terror birds, Titanis still had very long legs, particularly the lower legs and modified metatarsals (foot bones) that added extra length to the leg. This resulted in a digitigrade stance that essentially means that Titanis would have balanced upon its toes rather than the flats of it feet (like humans do). All together the leg construction resulted in increased mechanical advantage from the levering of longer leg and foot bones as well as a longer stride that allowed Titanis to cover more ground with each step. This would have allowed for a very efficient means of locomotion that would have allowed Titanis to run down prey, as well as being potentially more manoeuvrable thanks to its bipedal stance and short frame that would have allowed for tighter turning. Reconstruction of the inner ears also shows that Titanis had a well-developed sense of balance.

Assuming that Titanis’s skull was similar to other phorusrhacids, and currently there is no reason to think that it was not, then the beak would have been the primary killing weapon. The tip of the beak would have been strongly curved down to a sharp point, as can be seen in other carnivorous birds today. In feeding this hook tip pulls at the meat while the lower jaw closes, shearing through the meat so that the bird has a bite sized chunk. In actual killing however the point could be brought down onto the neck or the back of the prey’s skull. This penetrating strike could hit an artery, damage the spine and even pierce the cranium and enter the brain causing instant death to the prey in question.

Smaller prey may have actually been swallowed whole, although observation of seriema birds suggests that small prey may have been thrown against the ground to stun or kill it outright before it was swallowed. Impacts against a hard ground would also break the bones of smaller prey resulting in easier swallowing. It’s also possible that Titanis may have regurgitated gastric pellets, especially after feeding on whole animals. This is seen today in owls which typically swallow rodents whole but are unable to digest the fur and the bones. After the bird has finished digesting the flesh, the bones and fur are packed together inside the stomach and are then brought up and regurgitated in the form of a pellet.

Extinction

The fact that Titanis existed for at least three million years, and also comes from a lineage of birds that lasted even longer, has led to a lot of thought as to what could have caused it to go extinct. Because Titanis was a fast runner and capable of tackling anything from small to medium and possibly even some larger prey, it seems unlikely that the cause could have been a loss of prey species. A possible alternative could be competition from newly evolving predators such as larger big cats as well as new forms of canids including the rising numbers of wolves which would have been hunting in packs. These new predators may have begun to displace Titanis as the top predator of its ecosystem, with other carnivores such as Arctodus (better known as the short faced bear) denying Titanis ready access to carrion from these other predators’ kills as well.

Another possibility that may have had a part in the downfall of Titanis is a changing climate. A trend of global cooling that happened in the Pliocene resulted in the climate of the Americas shifting from forest to drier open savannahs. Titanis was not just big it was tall, and when travelling in open grassland it could have easily been spotted by grazing herbivores who would have had plenty of warning to get away. This meant that Titanis would have steadily become a less successful predator, and even when it was successful it may have had to expend even greater amounts of energy when chasing prey. This situation combined with new predators that were better adapted to make use of the environment in their hunting may have combined to steadily overwhelm Titanis to the point where it could not continue to survive.

Further Reading

– A Giant Flightless Bird from the Pleistocene of Florida. – The Auk 80(2):111-115 – P. Brodkorb – 1963. – The wing of Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Late Blancan of Florida – Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History, Biological Sciences 36: 175–180. – R. M. Chandler – 1994. – The giant flightless bird Titanis walleri (Aves: Phorusrhacidae) from the Pleistocene coastal plain of South Texas. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15 (4): 842–844 – J. A. Baskin – 1995. – Systematic revision of the Phorusrhacidae (Aves: Ralliformes) – Pap�is Avulsos de Zoologia 43 (4): 55–91 – H. M. F. Alvarenga & e. H�fling – 2003. – Titanis walleri: bones of contention – Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 45: 201–229. – Gina C. Gould & Irvy R. Quitmyer – 2005. – Refined age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) from Florida and Texas using rare earth elements – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (3): 92A (Supplement). – B. McFadden, J. Labs-Hochstein, R. C. Hulbert Jr, J. A. Baskin – 2006. – Revised age of the late Neogene terror bird (Titanis) in North America during the Great American Interchange – Geology 35 (2): 123–126 – B. McFadden, J. Labs-Hochstein, R. C. Hulbert Jr, J. A. Baskin – 2007.