In Depth

Classification and controversy of validity.

Stenonychosaurus is a genus of troodontid dinosaur that spent much of its time depicted as a synonym to Troodon. Stenonychosaurus itself was first named in 1932 and for much of the twentieth century it was occasionally depicted as a small predatory dinosaur. Stenonychosaurus would also become the inspiration of Dale Russel’s ‘dinosauroid’ (see below). However, in 1987, palaeontologist Philip Currie wrote a paper detailing how differences in teeth and jaw structure observed in Stenonychosaurus and Troodon were simply down to age and growth stages. Because Troodon was named earlier in 1856, Stenonychosaurus became a synonym to the type genus of the Troodontidae.

Declaring Stenonychosaurus as a synonym was controversial, mostly because the Troodon genus had been established upon the description of just teeth. A further idea that all troodontid dinosaur material was referable to the Troodon genus was also problematic as it meant referring fossils from many different locations and slightly varying ages to one type of dinosaur. Still, despite the misgivings of many palaeontologists (including Philip Currie himself), Troodon, recreated with Stenonychosaurus fossils was commonly seen in dinosaur documentaries and books for the following thirty years.

By 2017 however things could not continue as they were. Troodon was first described as a ‘tooth taxon (known only from teeth), and continuing study of fossils attributable to Troodon not only failed to establish a clear irrefutable link between Stenonychosaurus and Troodon, differences in the fossils themselves also proved that they represented multiple genera, not one genus of troodontid. Subsequent papers in 2017 (Evans et al, van der Reest & Currie) confirmed this analysis, leaving Troodon to go back to being a tooth taxon, and Stenonychosaurus resurrected as a valid genus.

Not all fossils that have been attributed to Stenonychosaurus and Troodon have been moved over to Stenonychosaurus however. Once associated with these genera, fossils of a particularly large type of troodontid dinosaur have been used to establish a new genus named Latenivenatrix. This assessment is backed upon by several identifiable differences between the fossils of Latenivenatrix and Stenonychosaurus.Stenonychosaurus the Dinosaur.

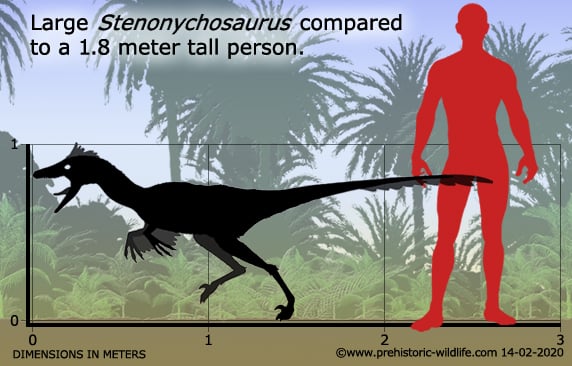

Stenonychosaurus was a typically built troodontid, ranging between two and two and half meters in length. A sickle shaped claw was present on each foot, and like relative genera, probably the primary hunting/killing tool of this dinosaur. Much of the later research done in the name of Troodon is referable to the Stenonychosaurus genus, and it’s worth remembering that these works are still about the same animal, only our name for it has changed.

Stenonychosaurus is noted for having a very large brain, one that in terms of proportions is much larger than most other dinosaurs. It is also known that Stenonychosaurus had large eyes, again proportionately larger than many other similarly sized dinosaurs. The combination of large eyes and large brains leads to a very tempting analysis that Stenonychosaurus was a strongly visually oriented predator. The large eyes could absorb more light, especially low levels, such as at night time the moon and stars were the only sources of light. A larger brain might not just have allowed for greater image processing, but spacial reasoning, allowing Stenonychosaurus to ‘figure out’ its environment, and be able to anticipate where to be before prey got there instead of just mindlessly following behind it. Ultimately however, we still do not know the full extent of Stenonychosaurus brain function, but who can say what further research will reveal.

The long legs and lightweight build of Stenonychosaurus show without doubt that Stenonychosaurus was built for speed and agility. It is probable that Stenonychosaurus hunted smaller creatures such as lizards and primitive mammals which would have all been plentiful and enough sustenance to maintain a dinosaur the size of Stenonychosaurus. There were also other types of small dinosaur and juveniles of larger species that would have also been within the predatory scope of Stenonychosaurus.

Troodontids however have sometimes been imagined to hunt if not in packs, but in loosely knit groups. This does not necessarily mean a group of Stenonychosaurus working together in an elaborate plan to hunt other dinosaurs, but if for example a sick hadrosaur caught the attention of several Stenonychosaurus, then several individuals might attack it in behaviour known as mobbing. This is where several predators realising an animal is weak attack it all at once, but with each one making an individual choice to attack rather than hunting to help other associates (like in lions). Mobbing behaviour has been observed in some birds, and if Stenonychosaurus (and other dinosaurs) did this on occasion, they might have split up afterwards and gone their separate ways, combining with different individuals if the opportunity to take larger prey arose again. The Dinosauroid proposal.

The idea of dinosaurs with increasing intelligence and dexterous hands has led many to wonder how dinosaurs like Stenonychosaurus would have evolved had the KT extinction which marks the end of the dinosaurs not occurred. Well in 1982 a palaeontologist named Dale Russell put form to the thought. Based upon Stenonychosaurus, Russell presented a humanoid dinosaur, which means that it was depicted as walking in a similar stance and posture as a human being. The body proportions were also close to that of a human. The eyes were still large, and the Dinosauroid was envisioned as giving birth to live young and feeding them upon regurgitated food.

Although some have criticised the reconstruction on the grounds that it is ‘too human’, and descendants of intelligent dinosaurs would have probably retained a more ‘classic’ theropod body, it is somewhat missing the point as the Dinosauroid reconstruction is more of a ‘what if’ than an absolute. Choosing a more humanoid bipedal posture at least makes it easier for people to relate too, which in turns makes them think more about it. It is still worth thinking about though that mankind is thought to have evolved from apes over the course of hundreds of thousands of years. Imagine what a dinosaur already smarter than a Chimpanzee could do over sixty-five million

Further Reading

- Two new theropod dinosaurs from the Belly River Formation of Alberta. Canadian Field-Naturalist 46(5):99-105. - Charles M. Sternberg - 1932. - A new specimen of Stenonychosaurus from the Oldman Formation (Cretaceous) of Alberta. - Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 6:595-612. - D. A. Russel - 1969. - Reconstruction of the small Cretaceous theropod Stenonychosaurus inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid. - Syllogeus 37: 1–43. - D. A. Russel & R. S�guin - 1982. - Theropods of the Judith River Formation of Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada, by P. J. Currie. - In Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems. Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology, Drumheller, Alberta 52-60. - P. J. Currie & E. H. Koster (eds.) - 1987. - Bird-like characteristics of the jaws and teeth of troodontid theropods (Dinosauria, Saurischia). - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 7: 72–81. - P. J. Currie - 1987. - Bone microstructure of the Upper Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Troodon formosus. - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 13, 99-104. - D. V. Varricchio - 1993. - Denticle Morphometrics and a Possibly Omnivorous Feeding Habit for the Theropod Dinosaur Troodon. - Gaia 15. - Thomas R. Holtz, Daniel L. Brinkman & Christine L. Chandler - 1998. - Embryos and eggs for the Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Troodon formosus. - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (3): 564–576. - David J. Varricchio, John R. Horner & Frankie D. Jackson - 2002. - The last polar dinosaurs: high diversity of latest Cretaceous arctic dinosaurs in Russia. - Naturwissenschaften - P. Godefroit, L. Golovneva, S. Shchepetov, G. Garcia & P. Alekseev - 2008. - On the Occurrence of Exceptionally Large Teeth of Troodon (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Late Cretaceous of Northern Alaska. - Palaios volume 23 pp.322-328. - Anthony R. Fiorillo - 2008. - Description of two partial Troodon braincases from the Prince Creek Formation (Upper Cretaceous), North Slope Alaska. - Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29(1):178-187. - A. R. Fiorillo, R. S. Tykoski, P. J. Currie, P. J. McCarthy & P. Flaig - 2009. A new species of troodontid theropod (Dinosauria: Maniraptora) from the Horseshoe Canyon Formation (Maastrichtian) of Alberta, Canada. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 54 (8): 813–826. - D. C. Evans, T. M. Cullen, D. W. Larson & A. Rego - 2017. - Troodontids (Theropoda) from the Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, with a description of a unique new taxon: implications for deinonychosaur diversity in North America . Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 54:919-935. - A. J. van der Reest & P. J. Currie - 2017.