In Depth

With the exception of Triceratops, Styracosaurus is the ceratopsian dinosaur that most people are familiar with. In fact it could even be argued that Styracosaurus has had even greater exposure in popular media such as films, books and games. This popularity is all down to the very distinctive arrangement of horns that extend from the back of the neck frill coupled with a large nasal horn that gave Styracosaurus a fierce looking appearance even though it was a plant eater.Classification and species

Styracosaurus was first described from an almost complete skull that was recovered by Charles M. Sternberg from what is today known as the Dinosaur Park Formation. It was not until 1935 however that a subsequent visit to the site recovered the dentaries (lower jaws) and most of the post cranial skeleton as well. However even with just the skull it was clear to the describers that this specimen belonged to the Centrosaurinae group of ceratopsian dinosaurs. These are the ceratopsians typified by Centrosaurus which have reduced frills but increased horn growth which makes them markedly different to the chasmosaurine ceratopsians that are typified by Chasmosaurus which overall have reduced horns but increased frills.

Over the remaining course of the twentieth century further remains continued to be discovered by other palaeontologists, but many of these were slightly different to the type specimen that characterised the type species of Styracosaurus albertensis (which translates to English as ‘spiked lizard from Alberta’). This led to the establishment of new species for the type species, but as the number of species increased so did the controversy regarding their validity. This has led to more in depth study of fossils attributed to the genus which has subsequently resulted in only the type species being considered valid. S. parksi and S. sphenocerus are regarded the same as S. albertensis, and by extension the informally named ‘S. borealis’ which is an earlier name for S. parksi. Another informally named species ‘S. makeli’ is now attributed to Einiosaurus, while the species S. ovatus has been established as representing its own genus of Rubeosaurus.Why the horns and frill?

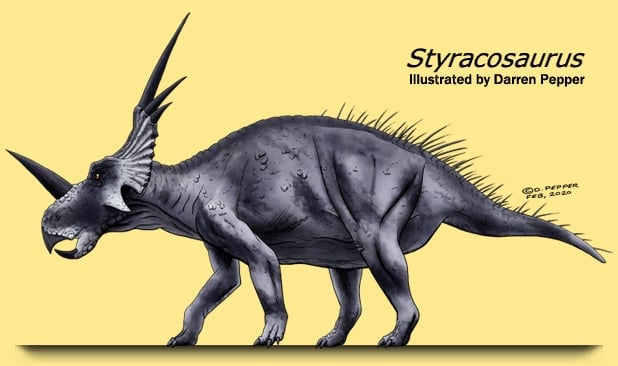

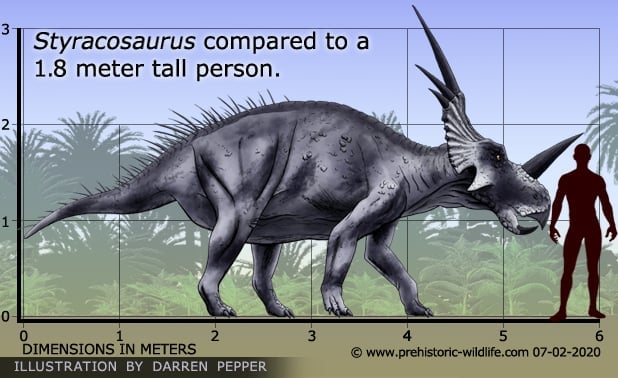

Most of the time different species and genera of ceratopsian dinosaurs are established by the arrangement, shape and signs of the horns and frill, but in Styracosaurus there does appear to be some confusion as there is a degree of individualism between specimens. Usually however Styracosaurus is depicted as having six large horns emerging from the upper portion of the neck frill. The upper pair point upwards and gently curve out to the sides, the lower two pairs point directly out to the sides. Other smaller horns are lower down as well as two large pointed jugals (cheek bones) that are commonly seen in other ceratopsians. A single large nasal horn rose upwards from the tip of the snout and was around sixty centimetres long, slightly larger than the largest frill horns. The frill itself was well developed to support the growth of the horns, but reduced in size overall, especially when compared to the large frills of the chasmosaurine ceratopsians.

The purpose and functions of the frill and horns is one of the longest running debates in palaeontology and has existed ever since the first ceratopsian dinosaurs were discovered. The idea that most people are familiar with is that Styracosaurus used its horns as weapons to protect itself from predators, but this idea is actually considered the least likely reason for them. One reason against is that the horns and frill only cover the head and neck, living the body with relatively little in the way of protection. Another is that horn and frill shapes were constantly changing and adapting amongst genera, sometimes even to the point where adaptions that were supposed to protect them became smaller or even disappeared, and this in the face of the development of even bigger and more powerful predators like tyrannosaurs. Logic would at least dictate that a successful anti-predator design would become stabilised and even enhanced like can be seen in the ankylosaurs.

Another theory is that the horns were actually anchor points for well-developed jaw muscles that would offer tremendous bite force for the shearing beak. Again however the problem of variation in ceratopsian forms exists, as different arrangements and shapes would result in different muscles and attachments between genera. Further to this is the observation that clear muscle attachments points are lacking. Another theory concerns thermoregulation where the frill allows for more rapid warming when faced into the early morning sun, and cooling during the heat of the day by offering a larger surface area for heat loss. This could in part explain the development of chasmosaurine ceratopsian that are better known from later in the Cretaceous which could have been warmer.

So far there is only one explanation which explains why Styracosaurus was different from other ceratopsians like Centrosaurus and Pachyrhinosaurus is display. When they first hatch, ceratopsians have underdeveloped horns which continually grow until the individual reaches maturity, which signals to others that they are old enough to reproduce. The problem then arises that there was not just one species of ceratopsian active at the time but possibly several together. In order to continue their species a ceratopsian like Styracosaurus needs to identify others of its kind, and this is where the distinctive head ornamentation comes in. For example; If a Styracosaurus ever met an Einiosaurus, it would know straight away that it was not the dinosaur it was looking for because Einiosaurus has just two large horns that rise from the back of the frill and a short nasal horn that curves round to point forwards. This would also work for the Einiosaurus, and by recognising each other in this way they would not waste time and energy trying to attract and court one another.

Whereas the horns allowed for quick identification of other species, the frill may have been the main signalling device for communicating with others of its species. The large fenestra (holes in the frill) would have supported a growth of skin and tissue, and its plausible that ceratopsian like Styracosaurus may have flushed blood into it to produce vivid colour displays that signalled their virility to others of their species. Some Styracosaurus skulls however do have damage that has been interpreted by some as being caused by the horns of rival Styracosaurus in dominance combat. However this damage has also been interpreted to being caused by parasites in a similar manner to how supposed tooth marks on tyrannosaur skulls have been caused. Supporters of the horns being used in combat with rival individuals however have suggested that the horns may have been used to try and score a hit on the side of the body rather than the head, with the more mature individuals with larger horns having a better chance of success.Styracosaurus the dinosaur

Like with other ceratopsians, Styracosaurus is interpreted as a low browsing herbivore that could eat anything from cycads to palms. Ceratopsians have in the past been seen as being large and heavy enough to knock down trees to get at the softer vegetation that grows in the tree canopy, although this view is not accepted by all palaeontologists. Also as in others, Styracosaurus cropped mouthfuls of food with its beak, although some speculate that it used its beak to grip and pull food rather than shear through it. The main processing took place at the back of the mouth where batteries of shearing teeth cut up plant matter into smaller pieces so that they could be more easily digested.

Styracosaurus also had the typical ceratopsian dinosaur shape with a stout body supported by all four legs. The rear legs were longer than the front legs which resulted in the hips being higher than the shoulder. There is still debate as to whether Styracosaurus like other ceratopsians supported its weight by keeping its legs directly beneath its body, or if the front legs sprawled out to the sides like in Computer modelling has suggested however that an intermediate position of the fore legs between sprawling and direct support was the most likely as it offered efficient locomotion with agility while browsing.

It has been commonly suggested that Styracosaurus lived in herds due to the presence of bonebeds that have numerous Styracosaurus individuals within them. Usually these bonebeds have been explained as a large number of individuals travelling and trying to cross a river swollen with flood water together, with many individuals drowning in the process. Some palaeontologists however have offered an alternative explanation of these collections by saying the remains of what were solitary individuals that clustered together around a watering hole in the dry season. When the last of the water disappeared the Styracosaurus had nowhere to go and so died of thirst en masse. Some deposits also suggest the presence of other dinosaurs amongst the Styracosaurus, but these remains could support either theory.

While the idea of Styracosaurus travelling in herds is all down to ones interpretation of the fossil deposits, it would be a worthwhile strategy for ceratopsian dinosaurs like Styracosaurus to stick together since large and powerful tyrannosaurs like Daspletosaurus were roaming the North American landscape at this time. Even with its horns one Styracosaurus would have a hard time defending itself from a predator like this, but several Styracosaurus clustered together in a form of phalanx would have been an incredibly difficult target for even a tyrannosaur to attack. The numbers involved would not have to be particularly high, just enough to cover one another.

The bonebed deposits of Styracosaurus have helped to establish at least one fact. The related Centrosaurus is also known from bonebed deposits that are similar in form to Styracosaurus, but always in older deposits. This means that Styracosaurus had the same ecological niche as Centrosaurus, but lived at a slightly later time, perhaps even being the dinosaur that replaced Centrosaurus.

Further Reading

– A new genus and species from the Belly River Formation of Alberta – Ottawa Naturalist 27: 109–116 – L. M. Lambe – 1913. – On dinosaurian reptiles from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana – Proceedings of the United States National Museum 77 (16): 1–39 – Charles W. Gilmore – 1930. – The skeleton of Styracosaurus with the description of a new species – American Museum novitates (New York City : The American Museum of Natural History). no. 955: 12 – Barnum Brown & Erich Maren Schlaikjer – 1937. – The behavioral significance of frill and horn morphology in ceratopsian dinosaurs – Evolution 29 (2): 353–361 – J. O. Farlow & P, Dodson – 1975. – Craniofacial ontogeny in centrosaurine dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ceratopsidae): taphonomic and behavioral phylogenetic implications – Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 121 (3): 293–337 – S. D. Sampson, M. J. Ryan & D. H. Tanke – 1997. – New centrosaurine ceratopsids from the late Campanian of Alberta and Montana and a review of contemporaneous and regional patterns of centrosaurine evolution – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 23 (3) – M. J. Ryan & A. P. Russel – 2003. – A revision of the late Campanian centrosaurine ceratopsid genus Styracosaurus from the Western Interior of North America – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (4): 944–962 – Michael J. Ryan, Robert Holmes & A. P. Russel – 2007. – New Material of “Styracosaurus” ovatus from the Two Medicine Formation of Montana – In: Michael J. Ryan, Brenda J. Chinnery-Allgeier, and David A. Eberth (eds), New Perspectives on Horned Dinosaurs: The Royal Tyrrell Museum Ceratopsian Symposium, Indiana University Press – Andrew T. McDonald & John R. Horner – 2010. – The postcranial skeleton of Styracosaurus albertensis – Kirtlandia 58:5-37 – R. B. Homes & M. J. Ryan – 2013. – Morphological variation and asymmetrical development in the skull of Styracosaurus albertensis. – Cretaceous Research. – R. B. Holmes, W. S. Persons, B. Singh Rupal, A. Jawad Qureshi & P. J. Currie – 2019.