In Depth

Dire wolves are extremely well known and are the single most common species of animal found at the world famous Rancho La brea Tar Pits.

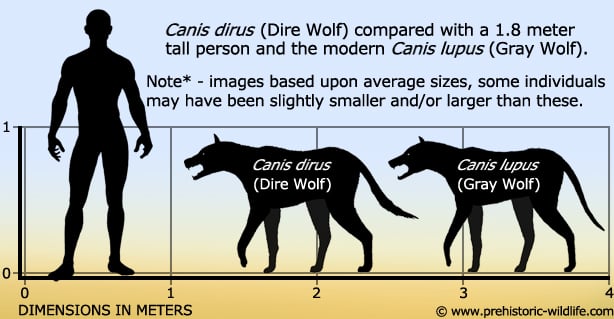

For a time of about one-hundred thousand years, the ranges of the dire wolf and gray wolf (Canis lupus) overlapped, and the two coexisted together.

The dire wolf however was larger and more powerfully built than the gray, and it’s thought that the two wolves focused upon different prey groups, thus avoiding direct competition with one another.

Because the gray wolf was smaller and more lightly built, it probably went for swifter and lighter prey items such as elk.

Dire wolves however had a much more robust skeleton which indicates the presence of much more powerful and larger muscles.

The skull is also proportionately wider indicating stronger bite muscles.

These adaptations in a predator are the tell-tale signs of a hunter that primarily concerned itself with larger and more powerful prey.

Further insights into dire wolf prey specialisation can be obtained through isotope analysis.

This process involves sampling a fossil, a destructive process that involves the sample being crushed, and then measured with a mass spectrometer to reveal the isotropic signature.

These signatures can be found in plants, the herbivores that ate them, and the carnivores that in turn ate the herbivores.

They can also be combined to recreate an environment revealing who ate what and who ate whom.

The analysis for dire wolves indicates that their primary diet was made up of a combination of horses and bison.

Only a small fraction was made up by other creatures, and this may have been through scavenging carcasses as opposed to hunting different animal species.

Dire wolves are generally considered to have been pack hunters like the gray wolves that were also active at the time.

Exactly how dire wolves behaved with one another is not one hundred per cent clear, but clues can be gleaned from the large amounts of available fossil evidence.

The huge amount of fossils recovered from Rancho La Brea have been interpreted by some that the dire wolf formed very large packs, that may in fact have featured more pack members than the packs formed by gray wolves that are active today and average four to seven wolves a pack, although the number of individuals can be much higher.

Larger packs and larger individuals would need increased amounts of sustenance, again pointing to a large prey specialisation, such as bison.

Many dire wolf fossils show signs of horrific injuries including completely broken fore legs and partially crushed skulls.

Remarkably however, many of these injuries actually healed with some of the fossils displaying evidence that the wolves in question lived for months and even years after the injury happening.

Furthermore, many of these specimens were recovered from Rancho La Brea, leading to the fact that the dire wolves in question died as a result of being stuck in the tar and not of the injury.

These types of injuries would almost certainly be the death of a solitary predator as they would be enough to prevent any animal from actively hunting.

As a pack member, an injured dire wolf may have been able to drag itself to a kill, although it may have had to wait for the others to finish.

Some have even speculated that the healthier wolves may have helped the injured by bringing them food while they recovered.

In comparison, this behaviour is not known in the gray wolf, but is seen in Lions.

A strong pack helps ensure the survival of all members, and if the above ever proves correct, it would be another example of the same behaviour being exhibited across two separate animal species.

Many dire wolf skulls also show teeth marks in the bone from where another dire wolf has caught it in its jaws.

This is suggestive of dominance behaviour in a group, as face and head biting is commonly seen in many pack living carnivores, including the gray wolf.

The severe lack of dire wolf pups in the fossil record is taken as a sign that the young were kept away from actively participating in hunts.

This is also seen in today’s wolves in what is usually referred to as a ‘rendezvous point’.

While the pack hunts, the pups stay at the rendezvous point awaiting the pack to return with food. Only when they are older do they begin travelling with the other pack members and participating with the hunts.

The dire wolf disappears from the fossil record at around ten-thousand years ago, the same time that much of the American Pleistocene megafauna such as Smilodon also disappeared.

There are many theories as to what caused the extinction of the megafauna, from an environment that changed too much too fast, to a comet exploding in space above North America.

One occurrence that does correspond with the disappearance is the arrival of the first humans in North America by crossing the Bering land bridge that at the time connected North America to Asia.

Theories associated with this arrival include being out competed by humans for available food sources, to humans bringing new strains of bacteria and disease with them, that the existing North American animals had no natural resistance against.

Whatever the exact cause or causes may be, the only relatively safe thing that can be said about the disappearance of dire wolves is that if was almost certainly connected with the reduction and loss of their favoured prey species.

Without these, the dire wolf would have had to hunt smaller prey that was probably faster, and provided less sustenance than the heavily built dire wolf required.

But since the gray wolf was already suited to these types of prey, it survived into the modern era.

A 2021 study (Perri et al) tested DNA samples from dire wolves.

The result of these tests was that at a DNA level, Dire wolves were actually different to those of the Canis lineage.

This led to the establishment of the Aenocyon genus for Dire wolves.

Further Reading

- Temporal variation in tooth fracture among Rancho La Brea dire wolves. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (2): 423. – W. J. Binder, E. N. Thompson & B. Van Valkenburgh – 2002.

- Sexual dimorphism, social behavior, and intrasexual competition in large Pleistocene carnivorans. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22: 164 – B. Van Valkenburgh & T. Sacco – 2002.

- Bite club: Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272 (1563): 619–25. – S. Wroe, C. McHenry & J. Thomason – 2005.

- New body mass estimates for Canis dirus, the extinct Pleistocene dire wolf. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26: 209. – W. Anyonge& C. Roman – 2006.

- Craniofacial morphology and feeding behavior in Canis dirus, the extinct Pleistocene dire wolf. – Journal of Zoology 269 (3): 309–316. – W. Anyonge & A. Baker – 2006.

- Carnivore-specific stable isotope variables and variation in the foraging ecology of modern and ancient wolf populations: case studies from Isle Royale, Minnesota, and La Brea – Canadian Journal of Zoology 85: 458-471 – K. Fox-Dobbs, J. K. Bump, R. O. Peterson, D. L. Fox & P. L. Koch – 2007.

- Megafaunal Extinctions and the Disappearance of a Specialized Wolf Ecomorph – vol 17 issue 13, p1146-1150. – Jennifer A. Leonard, Carles Vila, Kena Fox-Dobbs, Paul L. Koch, Robert K. Wayne & Blair Van Valkenburgh – 2007.

- Quaternary records of the dire wolf, Canis dirus, in North and South America. – Boreas 28 (3): 375–385. – R. G. Dunda – 2008.

- Dire Wolf, Canis dirus (mammalia; Carnivora; Canidae), from the Late Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) of East-Central Sonora, Mexico. – The Southwest Naturalist 54 (1): 74–81. – John-Paul Hodnett, Jim I. Mead & A. baez – 2009.

- Dire Wolf, Canis dirus (Mammalia; Carnivora; Canidae), from the Late Pleistocene (Rancholabrean) of East-Central Sonora, Mexico – The Southwestern Naturalist 54.1: 74–81. – John-Paul M. Hodnett, Jim I. Mead, A. Baez – 2009.

- A comparison of tooth wear and breakage in Rancho La Brea sabertooth cats and dire wolves across time. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (1): 255–261. – Wendy J. Binder & Blaire Van Valkenburgh – 2010.

- The carnivoran fauna of Rancho La Brea: Average or aberrant?. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 329-330: 118–123. – Brianna K. McHorse, John D. Orcutt & Edward B. Davis – 2012.

- Cranial morphometrics of the dire wolf, Canis dirus, at Rancho La Brea: temporal variability and its links to nutrient stress and climate. – Palaeontologia Electronica. 17 (1): 1–24. – F.Robin O’Keefe, Wendy J. Binder, Stephen R. Frost, Rudyard W.Sadlier & Blaire Van Valkenburgh – 2014.

- Dire wolves were the last of an ancient New World canid lineage. – Nature. 591 (7848): 87–91. – Perri et al – 2021.