In Depth

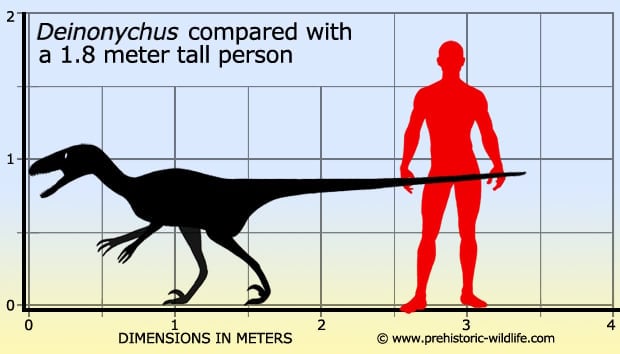

Although Deinonychus was first discovered in 1931, it would not be until the 1960s with the advent of more discoveries that it would get named and studied in detail. These studies helped lead to one of the most radical ideas put forward in the field of palaeontology; at least some of the dinosaurs were warm blooded.

Dinosaurs had always been compared to the reptiles of today which are always slow and sluggish until they can warm themselves up by exposing themselves to heat sources such as basking in strong sunlight. Dinosaurs as a whole had always been considered to be ‘just big lizards’ but smaller Dinosaurs such as Deinonychus were built to be very small and very fast. Such a lifestyle necessitates the need for a faster metabolism. This in turn is better provided for by being warm blooded, which in turn again requires adaptations for conserving body heat. While there is no direct evidence to support the placement of feathers on Deinonychus, it is a member of the dromaeosaur family, whose members through other fossil evidence are accepted to have had feathers. It would actually be very surprising if Deinonychus did not have feathers.

When first discovered the skulls of Deinonychus were fragmented and in a state of poor preservation, giving rise to an appearance not unlike Allosaurus. Later, more and better preserved skull material brought in a re-construction that had the skull being similar to that of Dromaeosaurus, yet still not as robust. The palate was strongly vaulted allowing for a narrowing of the snout, which in turn allowed for improved stereoscopic version. This means that Deinonychus had very good depth perception allowing it to gauge distances of prey items with greater accuracy. The jugals on the skull were wide to accommodate the strong biting muscles and it is generally accepted that larger individuals could easily bite through bone. The skull has very large fenestrae, including two in the lower jaw that would line up beneath the orbital fenestra when the mouth was closed.

The tail is constructed in a similar way to other members of its group with each tendon overlapping several vertebrae, making the tail a rigid ‘pole’ that could only move at the base. This could be used as a counterbalance when running and turning at speed helping to close the gap on prey items before they could run away.

Many palaeontologists (although not all) consider Deinonychus to have hunted in packs. Evidence for this comes from the frequent remains of Deinonychus found around Tenontosaurus fossils. Tenontosaurus is much larger than Deinonychus, and a single animal would have had great difficulty in taking down an adult Tenontosaurus. This has led to the pack hunter theory, although doubters of the theory have claimed it could just be an example of mobbing behaviour, or many Deinonychus scavenging the kill of a larger carnivore.

Deinonychus was well suited for using its forelimbs to grasp onto its prey, but like with Velociraptor, the ‘killing claw’ on the second toe of each foot seems to be better suited for stabbing than slashing. It could be that the claw was used to stab at a critical spot such as the neck. It may even have been used as a defence against others of its species for territorial defence or in pack domination fights. The only thing that we can be relatively sure of is that the old idea of a Deinonychus slashing open a dinosaurs belly in a single stroke is not very likely. One little thing of note about the claw is that it seems to have been held back so that it did not hit the ground while it was walking. This does prove that Deinonychus did at least have a special purpose for the claw.

Further Reading

– Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus, an unusual theropod from the Lower Cretaceous of Montana. – Peabody Museum of Natural History Bulletin. 30: 1–165. – John H. Ostrom – 1969. – The Pectoral Girdle and Forelimb Function of Deinonychus (Reptilia: Saurischia) : A Correction. – Postilla, Peabody Museum of Natural History Bulletin. 165: 1–11. – John H. Ostrom – 1974. – On a new specimen of the Lower Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Deinonychus antirrhopus. – Breviora. 439: 1–21. – John H. Ostrom – 1976. – New Material of Deinonychus (Dinosauria, Theropoda). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (3): 51A – William D.Maxwell & Lawrence M. Witmer – 1996. – The skull of Deinonychus (Dinosauria:Theropoda): New insights and implications”. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 16 (3): 73A. – Lawrence M. Witmer & William D.Maxwell – 1996 – First occurrence of Deinonychus antirrhopus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous: Aptian–Albian) of Oklahoma. – Oklahoma Geological Survey Bulletin. 146: 1–27. – D. L. Brinkman, R. L. Cifelli & N. J. Czaplewski – 1998. – Association between a specimen of Deinonychus antirrhopus and theropod eggshell, P. J. Makovicky & G. Grellet-Tinner. In First international symposium on dinosaur eggs and babies, Isona i Conca Dell� Catalonia, Spain, A. M. Bravo & T. Reyes (eds.) – 2000. – A possible egg of the dromaeosaur Deinonychus antirrhopus: phylogenetic and biological implications. – Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 43 (6): 705–719. – G. Grellet-Tinner & P. Makovicky – 2006. – Comparison of Forelimb Function Between Deinonychus And Bambiraptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae). – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 897–906. – Phil Senter – 2006. – Further Descriptions of the Osteology of Deinonychus antirrhopus (Saurischia, Theropoda). – Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences. 38. – W. L. Parsons & K. M. Parsons – 2009. – A description of Deinonychus antirrhopus bite marks and estimates of bite force using tooth indentation simulations. – Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (4): 1169–1177. – P. M. Gignac, P. J. Makovicky, G. M. Erickson & R. P. Walsh – 2010. – Ontogenetic dietary shifts in Deinonychus antirrhopus (Theropoda; Dromaeosauridae): Insights into the ecology and social behavior of raptorial dinosaurs through stable isotope analysis. – Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 552: 109780 – J. A. Frederickson, M. H. Engel & R. L. Cifelli – 2020.