In Depth

Fist named in 1850, Archaeotherium remains one of the best represented entelodonts in the fossil record. Archaeotherium is one of the earlier entelodonts and lived in North America at a time when the landscape was occupied by primitive horses, camels and rhinos and the only real predatory competition it faced were creodonts like Hyaenodon.

As with other entelodonts, Archaeotherium had enlarged neural spines on its forward dorsal vertebrae that allowed support for more powerful neck muscles, which in turn supported the oversized skull. This made Archaeotherium tallest and bulkiest at its fore quarters where its centre of balance would have been. This also would have made Archaeotherium surprisingly nimble on its feet as it would be able to pivot around on the spot rather than having to step forwards or back out to move.

As with other entelodonts, the skull of Archaeotherium was long with wide cheek bones. The jaws could open incredibly wide which suggests that Archaeotherium may have frequently closed them around other animals, perhaps even other members of its species in things like dominance contests. The large canines at the front of the mouth would have been potent weapons that could have quite easily punctured a cranium. It is also likely that the forward canine teeth were used as tools for tearing off and picking up pieces of food that were then tossed to the back teeth with a flick of the head. Here the sharper premolars could cut and crush food into smaller pieces that allowed for more efficient digestion.

Reconstructions and studies of the brain have indicated that while Archaeotherium did not have a high level of reasoning (meaning it would have followed set patterns of behaviour regardless of the situation), it did have a strongly developed olfactory area. Combined with long nasal passages from the longer skull, this would have allowed Archaeotherium to conduct much more detailed sampling of the air to detect scents of things that were both far off and perhaps obscured from view. This is similar to modern pigs which are considered to have some of the most sophisticated olfactory abilities in the animal kingdom.

While smell was the primary sense that Archaeotherium relied upon, it would have also had good eye sight. Forward facing eyes would have granted Archaeotherium stereoscopic vision that would have allowed it to gauge distances between itself and where it wanted to be. This would have been of vital importance when Archaeotherium had to deal with another animal, as it would allow it judge when and how far to move to time its strikes.

Further Reading

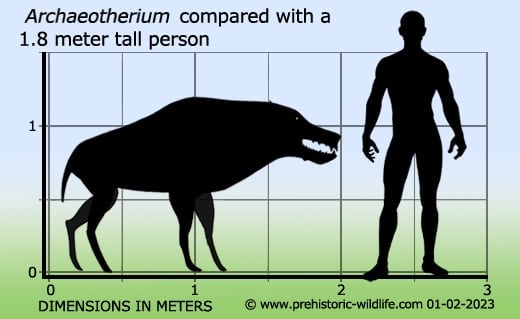

Archaeotherium has done a lot to increase our understanding of the entelodonts, but here it is not its bones but its foot prints that have revealed clues. At the Toadstool Geologic Park in Nebraska there are several sets of fossil footprints from many different animals. One set is of an ancient rhinoceros that shows that the living animal suddenly went from casually walking to running at what appears to tie in with the onset of the detection of an incoming predator. Another set of tracks that run parallel to the rhinoceros tracks suggests that a creodont like Hyaenodon was stalking the rhino. A third set of tracks from an entelodont are also present, but these have a different approach in that they maintain a zigzag pattern across the ground in the direction of the rhinoceros prints. Obviously the shortest and fastest route between two locations is the most direct, and zigzagging towards something is the antithesis to this principal. However no one ever said that the entelodonts was the one chasing this rhino. The zigzag pattern of footprints strongly suggests that the entelodonts was not chasing anything, but was simply going through the motions of a search pattern. By constantly changing direction the entelodont would pick up scents on the wind for everything from the animals, to fresh droppings, to even the smell of blood from a fresh kill. As such the entelodont was probably waiting for another predator to expend its energy upon making a kill and then zeroing in on the source of the smell of blood so that it could then use its large body and immensely powerful jaws to intimidate the other predator into giving up its kill. We cannot of course be certain if Archaeotherium was the exact genus of entelodont that left the footprints, but the location and age of the trackway does fit in within the range of Archaeotherium. At up to two metres long and over a meter tall at the shoulder Archaeotherium would have been a powerful animal, certainly capable of incapacitating a human had the two lived in the same time period. Despite this however, Archaeotherium was tiny when compared to genera like Entelodon and Daeodon.