Top Ten Predatory Mammals

A look at ten of some of the most dangerous mammalian predators to ever stalk the land. Much more detailed information is available upon each of these creatures, just click the names to go to them.

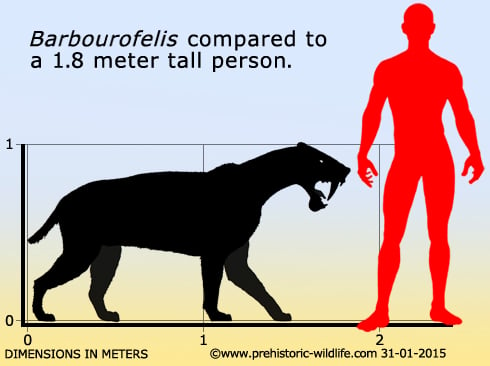

10 - Barbourofelis

Barbourofelis gets a mention on the grounds that it is the largest of the ‘false sabre-toothed cats’, so called because they were not actually cats at all, they just looked a lot like them. Barbourofelis was a particularly large individual with a powerful build that suggests it got close and physical with powerful prey before delivering a killing bite with its enlarged sabre-like upper canines. This means that although Barbourofelis was not a true big cat, it was still similar in both form and possibly behaviour to the larger machairodont sabre-toothed cats.

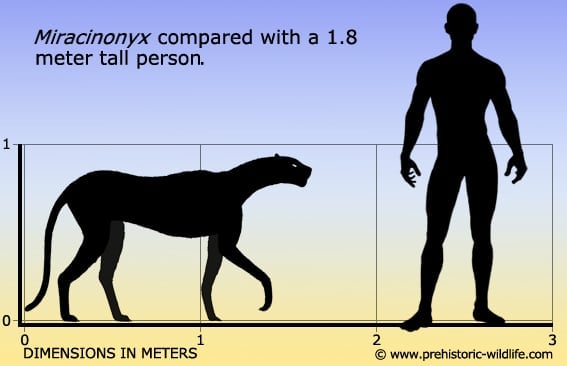

9 - Miracinonyx - a.k.a. the American cheetah

The

presence of Miracinonyx in North America is taken

as a case of amazing

convergent evolution. This is because Acinonyx,

the African

cheetah, is not thought to be related to Miracinonyx,

yet

Miracinonyx still evolved a body that was almost

identical to its

African counterpart. This suggests that Miracinonyx

wasn’t hunting

the larger and more powerful megafauna that other big cats were, and

was probably chasing animals like pronghorns (while the cheetah is

usually dubbed the fastest land mammal, pronghorns are actually

strong rivals to this title, and can actually maintain high speeds

longer than cheetahs can).

Miracinonyx

was well suited to life as a sprinter with some species having

partially retractable claws which meant that the claws did not slide

back when not in use (say, like a house cat). These claws would

have always been in contact with the ground, and like running spikes

they would have offered increased traction for faster and more

efficient locomotion. Miracinonyx also had an

enlarged nasal cavity

that allowed for a much faster rate of respiration so that its muscles

would not tire so quickly while running.

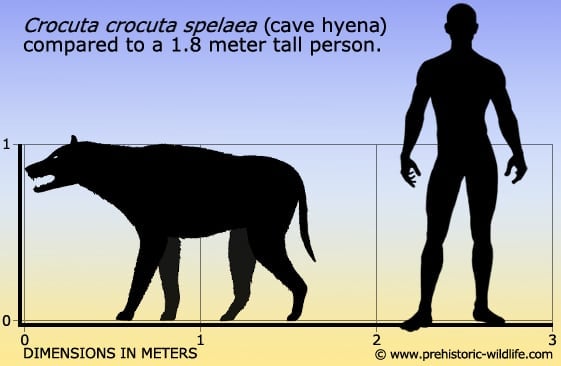

8 - Crocuta crocuta spelaea - a.k.a. Cave Hyena

Today

spotted hyenas are actually more feared than lions by some people,

but as recently as eleven thousand years ago a slightly larger sub

species called Crocuta crocuta spelaea

(sometimes classed as

Hyena spelaea) was one of the dominant carnivores

of Pleistocene

Eurasia. Popularly called the cave hyena this animal seems to have

scavenged most animals like hyenas do today, while also having a

penchant for hunting wild horses as well as woolly rhinos like

Coelodonta.

Cave hyenas also seem to have been capable of taking on

some of the most dangerous animals of this time such as the cave bear

Ursus

spelaeus, although these may be cases of

scavenging.

The

cave hyena like its modern counterparts is known to have attacked and

eaten early homonids like Neanderthals that cave hyenas would have also

competed with for cave space. Cave hyenas have also been seen to be

the reason why early humans could not cross the Bering Strait into

North America. Evidence to support this comes from the first signs of

Human settlement in Alaska coming from roughly the same time that the

cave hyena disappeared.

7 - Homotherium

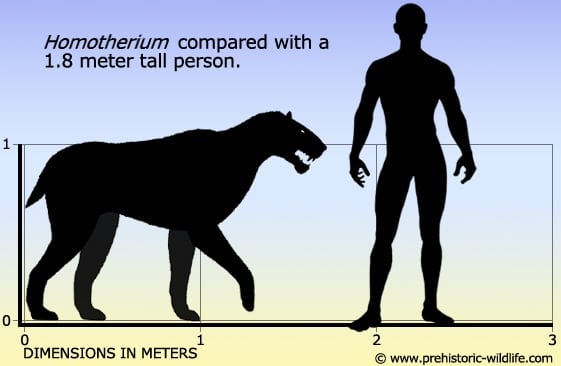

Although

a big cat, Homotherium was closer to a hyena in

its main body

proportions which saw it having much longer front legs that resulted in

a sloping back. As a scimitar-toothed cat Homotherium

had enlarged

upper canines similar to Smilodon, although not

so large that they

extended past the lower jaw. These teeth also had serrations that

meant they could easily slice through the tough hides of prey,

causing grievous wounds that poured blood. This blood loss would

incapacitate prey more effectively than if Homotherium

struggled with

it.

Homotherium

would have likely eaten a variety of animals when able, but as a

genus it seems to have had a particular preference for juvenile

mammoths. Mammoth remains, sometimes in large quantities, are

always known from areas where Homotherium has been

found, sometimes

in very close association. In Pleistocene times these areas would

have been grassy plains and steppes, but Homotherium

would have

had an advantage thanks to its long legs that not only allowed for more

energy efficient locomotion, but extra reach on large prey like

juvenile mammoths.

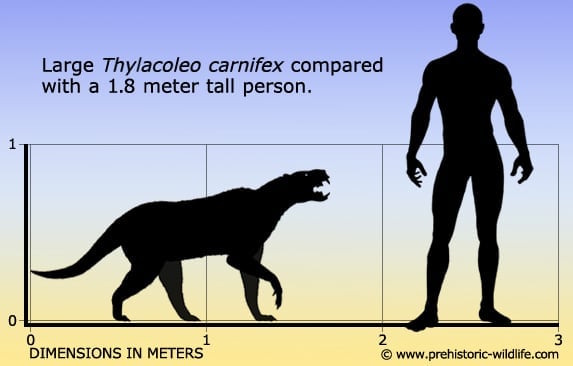

6 - Thylacoleo - a.k.a. the Marsupial lion

Today

Australia is world renowned for the large number of marsupials that

live there, but back in late Pliocene and Pleistocene periods a huge

predatory marsupial named Thylacoleo was one of the

apex predators of

the land. Thylacoleo has some of the most

specialised killing teeth

on this list which were oversized incisors that could slice through the

flesh of other mammals. At one time some palaeontologists suggested

that these teeth were used for cracking things like nuts, and that it

may actually been a herbivore. However new study of other herbivorous

animals has shown distinctive tooth marks that match up to the incisors

of Thylacoleo, once again strongly suggesting

that Thylacoleo was a

predator.

Aside

from the teeth Thylacoleo also had retractable

claws. Because the

claws were retracted when Thylacoleo was just

walking they remained

sharp so that they could be used for extra grip upon prey.

Additionally Thylacoleo also had an opposable

thumb for even more

grip, although it has also been suggested that these features may

have been adaptations for climbing.

5 - Panthera leo atrox - a.k.a. the American Lion

One

of if not the largest lion in the fossil record, the American lion

was one of the dominant predators of late Pleistocene North America.

Similar to its modern day counterpart the African lion, the American

lion would have hunted a variety of animals by using ambush tactics

to surprise and take down prey. However unlike the modern African

lion, it is not certain if it was a solitary or group hunter as

although interpretations of fossil evidence support a solitary

lifestyle, they do not conclusively prove that it only hunted alone.

On a side note however, cave art that depicts the slightly smaller

but closely related Eurasian cave lion (Panthera

leo spelaea)

depicts this lion hunting in groups which could hint to similar

behaviour in the American lion.

The

American lion has had and currently still has a complicated position

amongst other big cats as while most treat it as a sub species of the

African lion, others continue to class it as its own distinct

species. Unfortunately the fossil record is no clearer either since

the closest lion to the American lion, the Eurasian cave lion, also

has a similarly complicated taxonomic history.

4 - Hyaenodon

No modern relatives of Hyaenodon remain today as the creodont mammals that Hyaenodon belonged to waned and disappeared in the face of competition from the newly emerging dogs and big cats. In its day though Hyaenodon was one of the most devastating predators on the landscape that hunted everything from primitive horses to primitive rhinos, back before they even came close to the sizes that they grow to today. Key to Hyaenodon’s success was the immensely powerful crushing jaws which seem to have been used to literally crush the skulls of its prey. In addition to these jaws, Hyaenodon had slicing teeth at the back of its mouth that continually sharpened themselves throughout the animal’s life. This was achieved by the top and bottom teeth rotating against each other as the animal grew older so that they constantly ground together to produce a sharpened edge. This meant that even in old age, Hyaenodon could comfortably feed from animals while other older predators with badly worn teeth starved.

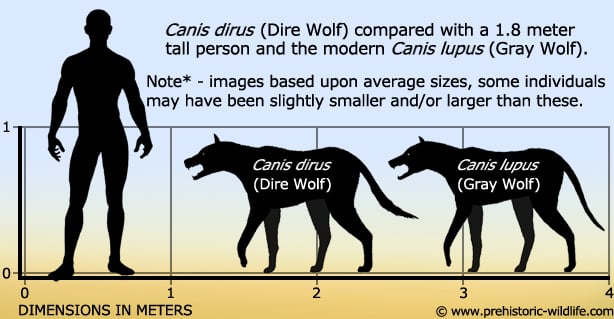

3 - Canis dirus - a.k.a. the Dire Wolf

Probably the most well-known and famous of the ancient wolves and with a name that means ‘dire’, Canis dirus is usually depicted as a monstrous hulking wolf much bigger than a person. In realty however the skeleton of Canis dirus wasn’t that much bigger than its relative Canis lupus, better known as the grey wolf that can be seen running around wild in parts of the northern hemisphere today. However, Canis dirus was a far more powerful wolf as indicated by the more robust bones and attachments for larger muscles. This pointed towards a specialisation towards much larger prey, much like its rival the sabre-toothed cat Smilodon ( which Canis dirus would have shared its habitat with. What many people also do not realise is that Canis dirus and Canis lupus actually co-existed on the same landscape until the disappearance of the North American megafauna towards the end of the Pleistocene. With the large prey gone, Canis dirus found itself hunting animals that were faster and providing less sustenance when caught, which resulted in its more powerful body actually becoming a hindrance. This is why Canis lupus, which is lighter and faster survived while Canis dirus went extinct.

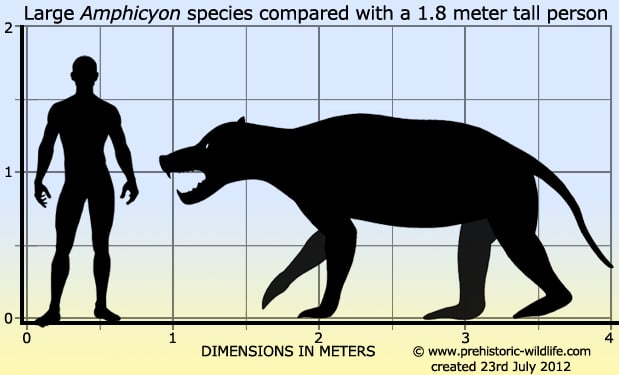

2 - Amphicyon - sometimes just called Bear dog

Amphicyon

had a number of things going for it as a predator including large

size, legs for running, powerful jaws and a greater level of

intelligence over the predators that were previously at the top of the

food chain before the appearance of bear dogs like Amphicyon.

These

adaptations were not just to compete with existing predators however,

but to take down larger, more powerful and faster running prey

animals that were replacing the previous prey.

Despite

the fact that Amphicyon was a powerful animal, it

would itself be

replaced by even more intelligent predators such as the early dogs that

would go onto develop new hunting strategies and behaviour.

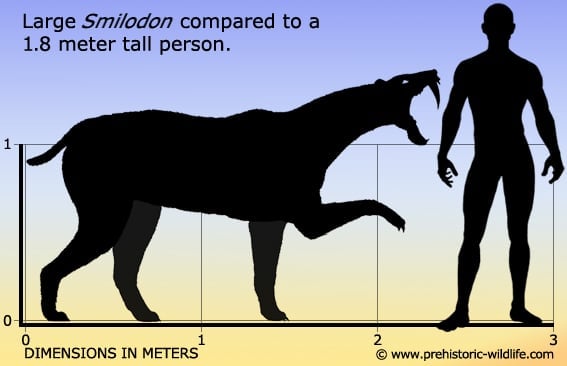

1 - Smilodon - a.k.a. the Sabre-toothed Cat

Without

doubt the most famous of the mammalian prehistoric predators,

Smilodon has been regularly depicted in both

documentaries and fantasy

pop culture alike. Smilodon itself however was a

specialised predator

of large and powerful animals, with in depth tests revealing it had a

preference for hunting bison. To deal with such large animals,

Smilodon had a very powerfully built forward body

that allowed it to

grip hold of the animal as it delivered a killing bite. The enlarged

sabre-like canine teeth that gave Smilodon its name

were certainly the

killing weapons that finished its prey, but they were also

surprisingly weak and Smilodon would have had to

first subdue its prey

by physical force before delivering the fatal bite.

Although

so far not known for certain, the large number of Smilodon

remains

from the La Brea Tar Pits in California suggest that this cat may have

hunted in packs, possibly family groups similar to today’s Lions in

Africa. This fits into the fact that large numbers of dire wolf

(see below) remains have also been recovered, while presumably

lone carnivores such as bears are only known in very small numbers.

Quick mentions

Arctodus

- a.k.a. the Short Faced Bear

Arctodus

has not made the list on the grounds that fossil evidence strongly

suggests that it was a specialist scavenger and not a predator that

made an effort to actually kill its own prey. Much more detailed

information about this is on the main Arctodus

page, just click the

link above.

Livyatan

& Basilosaurus

These

are whales and as such are obviously mammals, but this list is more

about terrestrial carnivores. More information about these whales can

be found on their pages, as well as on top

ten marine predators.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Random favourites

|

|

|