The early discoveries

Not long after the first European settlers arrived in New Zealand, stories about giant birds that once existed upon the Islands began to filter out, reaching all over the world.

The European settlers initially only had Maori stories to go on, but in time the remains of large flightless birds began to be found, and it was soon established that before the arrival of humans upon New Zealand, the moa were the largest terrestrial animals upon the islands of New Zealand.

In the early days of moa study, a lot of things were assumed about these birds, but almost two centuries of scientific study later, and a lot more detail about these birds is now known.

Taxonomics

The word moa is actually the Māori word for describing these birds.

This word is also both singular and plural, which means that a single moa standing in a field could be called a moa, whereas a whole bunch of these birds standing in a field would also be just called moa.

The word usage is the same as if you were using the word sheep.

The moa birds can be further divided into specific genera that in some cases can be further divided into species.

For the most part this article will describe the moa birds as just moa, but in some instances specific genera will be singled out.

We’re also going to avoid calling the genera and species by their more common names to try and avoid confusion, but the common names are added to the genus names in a list at the very end of the article.

Early on, moa genera suffered from what is now termed the ‘wastebasket taxon’ effect, which is where similar remains to those already named would be simply labelled as an additional species without too much further thought.

However it must be understood that this took place in the mid and latter half of the nineteenth century when the science of palaeontology was still in its infancy and it was difficult for researchers to stay up to date with new discoveries since global communications still largely had to be hand delivered.

This led to a great many species of moa being named and established, but many of these have now been dismissed as invalid.

Later palaeontologists began noticing that many remains from different locations actually were the same as those from other locations, and thus were the same as the aforementioned species.

Some also noticed that some species were actually juveniles of already named adults, and so the species lists shrank further.

The biggest insight came about however when male and female birds began to be more positively identified.

This led to the discovery that male moa birds tended to be smaller than female moa, yet at the time the male moa were being classed as different species by the first researchers of the nineteenth century because of the size difference.

This led to the final reduction of species named so that today only a handful of the once named species are considered to be valid, those which are not are now synonyms to these valid species.

New discoveries in the future may lead to the creation of new genera and species, but the existing moa bird remains are still giving up their secrets.

This is because many moa remains are actually still testable for DNA, and DNA analysis of some of these remains has revealed that although they are physically similar in appearance, they are slightly different to the DNA sampled from other remains, which indicates that they are actually different species.

Therefore the future of moa taxonomy is what you might term semi-fluid; the established genera and species are considered to be valid, but there may be further species lurking within them waiting to be discovered.

The moa have been assigned to the ratite family of birds which today are noted for being cursorial (ground dwelling) in their nature.

For a long time moa were thought to have been related to other flightless birds from New Zealand (Apteryx) such as the kiwi, cassowary (Casuarius), and even the Australian emu (Dromaius).

However in 2010 a study by Philips et al revealed that the closest known living relative of the moa birds are now actually living in South America and are known as tinamous.

This is surprising, not only because of the geographic distance of South America from New Zealand, but that the tinamou birds are not actually ratites, but form a closely related sister group called the Tinamiformes.

What were the moa like?

In the simplest terms the moa were heavily built birds that walked around on two powerfully built legs.

The leg proportions however do not match those of fast running birds which suggests that moa were relatively slow for their leg length.

It should be remembered however that there were no large ground predators known to have existed in New Zealand until the arrival of the first people, so the ability to run fast would have really been an unnecessary option anyway.

The moa are a good example of the extreme effects of being secondarily flightless.

The moa were certainly descended from ancestors that were capable of flight; it is the only way birds could have feasibly reached the islands of New Zealand.

Whereas many secondarily flightless birds still retained smaller versions of their ancestors wings however, the wings of the moa had completely disappeared.

Why some birds lose the ability to fly is always a matter of contention, but for the moa it seems that an abundant supply of food combined with no ground predators meant that there was simply no need to expend energy upon flying to escape or search for food

. Aside from losing their wings, the feathers on the body also devolved to more simple hair-like structures.

These would not have been capable of creating lift for flight, but they would have still performed an important insulatory function as well as allowing rain to run off the body without getting the skin wet.

Analysis of feather pigments has also revealed that moa could be quite variable in their colour, with the genus Dinornis having feathers that were red/brown in their colouration, to the genus Emeus which had feathers that were more of a beige colour.

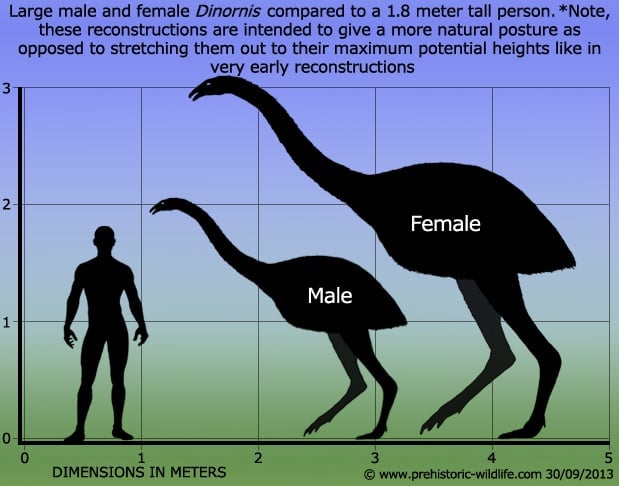

Due to their large physical size, especially genera such as Dinornis, early reconstructions of moa were usually done with the deliberate intention of making them appear as tall as possible.

This meant posing skeletons so that they were stood as erect as possible, with even the neck connecting to the base of the skull.

This was a mistake however given that the neck vertebrae actually connect to the back of the skull, indicating that the head was actually carried more forward from the body rather than above it.

This arrangement also allowed moa a broad range of motion, cropping at plants near the ground to reaching up to the lower branches of the tree canopy.

Moa birds are noted for having downward curving beaks that are often termed secateur like (secateurs are special pruning shears for snipping plant branches).

These beaks would allow moa to slice off choice parts of plants before swallowing the mouthful which was then processed further by gastroliths held within the gizzard.

Stomach contents and coprolites of moa birds have been analysed which reveal that moa would feed upon a variety of different plants, eating parts such as leaves and green twigs.

As already briefly mentioned above, the female moa were larger than the males.

In some genera the size difference was fairly slight, but in others the female could be anything between one and a half to twice as large as the male.

Moa breeding

Remains of eggs and juveniles all seem to indicate that the moa birds followed a k-strategy method when it came to survival.

What k-strategy means is that when moa raised young they would only attempt to raise one to two or three chicks at a time.

By only raising a small number, the parents could invest more time and attention in rearing the young, thus increasing their chances of surviving to adulthood.

Studies of bone grow growth of moa have revealed that it would take up to ten years for a moa bird to reach reproductive maturity.

The opposite of k-strategy is r-strategy, and this is where large amounts of young are born with the expectation that most will be killed by predators while a few will survive to adulthood and reproduce themselves.

Here the sheer weight of numbers ensures the species survival rather than parental ability.

The main drawback of a k-strategy method of reproduction is that population growth is always much slower, and hence populations take much longer to recover after sudden declines.

This might also explain why moa birds eventually went extinct after the ecosystems of New Zealand were upset by the arrival of the first people.

Moa seem to have preferred to nest amongst the shelter of rocks where interpretations state that parent birds scratched out notches in pumice (a form of solidified lava) with their toe claws.

After this they seem to have covered the nest with plant material to provide a soft and warm lining for incubating their eggs.

The size of the eggs depends upon the genus/species involved, but even smaller species eggs could be as much as twelve centimetres long, with eggs of larger species being up to twenty-four centimetres long.

Moa eggshells however were very thin for their size, around one millimetre thick, something which has led to reasonable speculation that male moa may have sat on and incubated the eggs since their smaller physical size meant that they were much lighter than the females, and hence less likely to accidentally cause damage to the eggshell.

The collected remains of eggshells and moa in some locations has led to reports of moa breeding in large colonies, however modern analysis and thinking suggests that these collections are the results of small amounts of remains steadily building up over a long period of time.

This is the same principal regarding the discovery of Pleistocene mammals in places like Europe, and in this respect we’ll quickly cover the now extinct cave bears (Ursus spelaeus).

Cave bears got their name from their fossils being discovered in cave deposits, and what excited the first discoverers of these remains is that fossils belonging to several hundred individuals were found within the cave sediments.

This led to early depictions of cave bears living in anything from a dozen to several hundred bears per cave at the same time.

Modern analysis of these remains however leads to a much more likely notion of there only ever being one bear (not including any young) living in a cave at any one time, but the cave being repeatedly inhabited by a successive line of bears after the death of the previous occupant.

Rock formations can remain unchanged for hundreds of thousands to millions of years, which means that a cave that provides a suitable shelter, may still be being used by the same species of animal one hundred thousand years later as long as it is largely unchanged.

For the sake of argument we’ll say that a cave bear could live for about twenty years on average before dying from natural courses.

Over a course of one hundred thousand years divided by an average lifespan of some twenty years, around five thousand individual bears could call that cave home during that time period, and assuming that they all died within that cave, their bones would all collect together into one seemingly huge deposit.

A few thousand years later and an eager naturalist discovers this accumulation of bones and suggests that some five thousand bears lived together in this cave, and you can appreciate how this misconception got started.

Back to New Zealand and the moa birds, and the same principal applies.

Suitable sheltered locations for rearing young would have been few and far between, so good spots would have been repeatedly used over and over the millennia by successive generations of moa.

The accumulated detritus of eggshell fragments and bones over these thousands of years could just as easily result in the false interpretation of these being breeding colonies as to what happened with the early interpretation of cave bears of Europe.

Moa mummies

Some of the most exciting finds relating to moa birds are the mummified remains of some individuals.

This are naturally preserved individuals that lived and died at high elevations where the moisture content of the air is far less than it is nearer sea level and in moist environments such as forests.

In addition, these locations are usually more exposed to prevailing winds which can accelerate the drying process further.

The main genera known to have mummified remains are Euryapteryx and Megalapteryx and between them these include soft tissues such as muscle and tendons, of the head, neck, leg and even a complete foot.

These mummified remains have offered researchers a rare glimpse into how exactly moa were put together beyond just their bones.

Predators of the moa

Prehistoric New Zealand during the Pleistocene was a land dominated by birds.

Mammals seems to be absent from New Zealand, though new discoveries coming to light as of 2013 seem to indicate that New Zealand may have actually had a population of small mammals.

The only definitively known native mammal is a bat, and the only other vertebrates were reptiles like the Tuatara.

After this there are of course invertebrates like insects, but none of these animals seem to have been capable of posing a threat to moa.

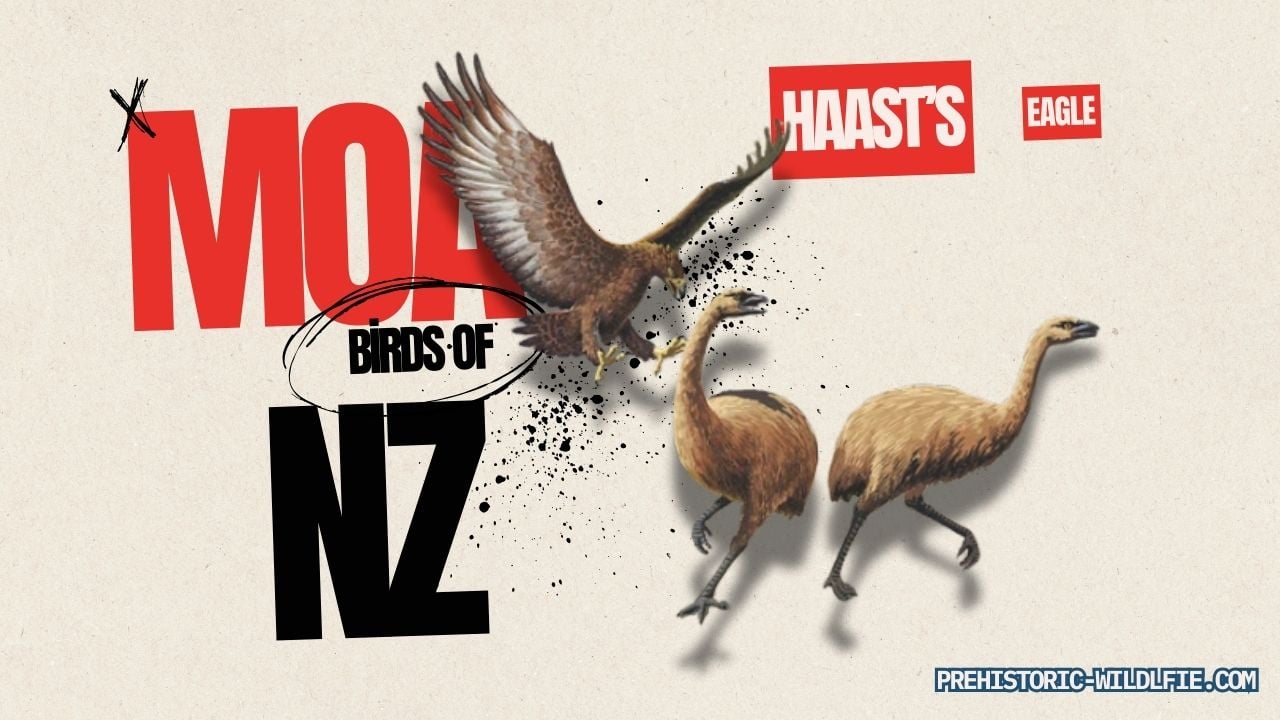

To find natural predators of the moa we have to look again to the birds, and here there is one serious contender that is believed to have hunted moa exclusively: the Haast’s eagle.

Big animals often have big predators, and while the Haast’s eagle may not have had a wingspan as large as some of today’s largest eagles, the Haast’s eagle was almost certainly the heaviest eagle that we know about to ever take to the air.

Female Haast’s eagles have been estimated to weigh in the range of ten to fifteen kilograms in weight, whereas the largest recorded eagle living in captivity (and hence well fed) only reached nine kilograms in weight.

The relatively short wingspan of the Haast’s eagle was actually one of its main advantages when it came to hunting moa.

In order to track down moa birds, Haast’s eagles would have been hunting and flying in forested environments, and a shorter wingspan meant that Haast’s eagles could fly amongst the trees without clipping their wings on them as they approached their targets.

Haast’s eagles are believed to have struck moa birds at high speeds, driving their powerful six to ten centimetre long talons into the spines of their prey, crippling them almost instantly.

There is also another bird that may have hunted moa, and this is the Eyles’ harrier.

Although no way near as large as the Haast’s eagle, the Eyles harrier was still large enough to be a threat to small juvenile moa that may have strayed too far from their parents.

Both the Haast’s eagle and the Eyles harrier are now extinct, though they seem to have gone at different times.

The Haast’s eagle disappears at some point soon after 1400AD, the same time as the moa largely disappeared.

This indicates that the Haast’s eagle was a specialist at hunting the moa, and when they disappeared, they were unable to adapt to a new prey source.

Eyles’ harriers however are thought to have been generalists and while capable of hunting small individual juveniles, they likely also hunted other types of birds.

However, as the environments of New Zealand and available prey birds changed and declined, they too disappeared.

Extinction of the moa

Around 1250-1300AD the proverbial death knell was sounded for the moa when the first humans reached New Zealand.

The moa were apparently quite docile in nature, something that came about from the lack of large ground predators in New Zealand up until that point.

Finding themselves in a new land the first people there, the Māori, needed food to eat, and the presence of large birds that could feed many people and did not immediately run away would have been the obvious choice.

Human hunting was not the only factor to contribute to the demise of the moa, habitat destruction would have also been a further strain upon them.

New populations of people need to clear land to build settlements, and eventually clear more to grow plants to eat.

There were two further additions to the moa survival problem caused by the arrival of the first people.

First was the kuri, also known as the Polynesian dog, and apart from being used by hunters to assist in hunting moa, feral populations of these dogs may have also formed packs and hunted moa and other ground dwelling birds of their own accord.

Second, was the introduction of the Polynesian rat, a more accidental arrival but one that could have fed upon unattended eggs and newly hatched chicks incapable of running away.

As already mentioned above, moa birds followed a k-strategy survival method.

With large numbers of moa being killed off for food, the population simply could not grow fast enough to replenish the numbers lost from hunting.

A further factor is that as the numbers declined fewer opportunities were there for individuals to pair up, meaning that incidents of breeding actually happening began to decline as well.

With the pressure on the moa unrelenting, their populations quickly reached a point where they could not recover in the face of a changed ecosystem.

The most recent confirmed moa fossils are dated to around the year 1400AD, and it was also at about this time that the fossils of the main indigenous predator of the moa, the Haast’s Eagle disappeared.

Aside from further underlining the intimate predator/prey relationship between these birds, this also indicates that by this time moa where very scarce.

Not everyone is convinced however that the moa died out at this time or indeed that they are extinct at all.

Survivors? (sightings and cloning)

As far as hard science is concerned, the moa perished around the year 1400AD, possibly lasting up to a few decades after.

This date is easy to accept because there is a lot of evidence to support it, namely, a lot of moa remains go up to this point and then rather suddenly drop off.

However, it is possible that some moa existed past this mark, the question is, how far?

There have been isolated reports of people encountering moa in some of the remotest regions of New Zealand all the way up until the end of the nineteenth century.

These have come from Maori hunters stalking animals through the countryside, sailors sighting moa on coastlines to farmers spotting a moa as they managed their land.

Even footprints have occasionally been reported.

Unfortunately, there is no hard evidence such as photographs to confirm any of these sightings, although granted, back in those days camera equipment was very new and only owned by a small number of people.

By contrast today, almost every single person possesses the capacity to document sightings, even if only with a mobile phone camera.

There have however been claims of footprints to even photographs of objects that are claimed to be living moa that have managed to survive into modern times.

Unfortunately these photographs, just like those claiming to depict mammoths in the Russian Federation, or Bigfoot in North America are almost always so blurry and at such extreme distances that nothing can be clearly defined and identified.

You have to appreciate that often hoaxes get made just to see how many people can be fooled, and now that image editing software like Photoshop is more available to everyday people instead of just professionals, it is easier than ever to create images.

Assuming that no malicious intent is intended, misidentification is also another factor.

A small bird with moa-like proportions gets photographed in such a way that it appears to be a much larger bird seen from further away.

An analogy to the above would be reports of big cats roaming the British Isles.

Although authorities concede that it is probable that some big cats like leopards were released into the British countryside after the introduction of the Dangerous Wild Animals Act in 1976 which required keepers of these animals to have a special license, many photographs of animals supposedly depicting predators like leopards and panthers have later been revealed to be nothing more than domestic house cats shot against backdrops that at range coincidentally make them appear to be bigger than they actually are.

Perhaps a more exciting prospect for the future would be the possibility of genetic cloning.

The relatively high state of preservation of some moa remains have allowed for genome mapping to take place, and with continuing advances in genetic engineering, most scientists concede that it will only be a matter of time before an attempt is made to resurrect a long extinct animal, and with the available remains known, the moa birds may one day be possible candidates for this.

List of some moa genera and their more common names

- Anomalopteryx - a.k.a. Lesser Moa, Little Bush Moa, Bush Moa.

- Dinornis - North Island Giant Moa (D. novaezealandiae), South Island Giant Moa (D. robustus).

- Emeus - Eastern Moa.

- Euryapteryx - a.k.a. Coastal Moa, Broad Billed moa and Stout Legged Moa.

- Megalapteryx - Upland Moa.

- Pachyornis - Heavy-footed Moa (P. elephantopus), Mantell’s Moa (P. geranoides), and Crested Moa (P. australis).

Further reading

- On the remains of Dinornis, an extinct gigantic struthious bird - Richard Owen - 1843.

- Description of Dinornis crassus - Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1846: 46 - Richard Owen - 1846.

- Avium systema naturale - Expedition der vollst�ndigsten Naturgeschichte - Ludwig Reichenbach - 1852.

- Genus Pachyornis - Catalogue of the Fossil Birds in the British Museum (Natural History) - Richard Lydekker - 1891.

- The diet of moas based on gizzard contents samples from Pyramid Valley, North Canterbury, and Scaifes Lagoon, Lake Wanaka, Otago – Records of the Canterbury Museum 9: 309–336. – Colin James Burrows, Beverley McCulloch & Michael Malthus Trotter – 1981.

- And then there were twelve: the taxonomic status of Anomalopteryx oweni (Aves: Dinornithidae) – Notornis 29 (1): 165–170 – P. R. Millener – 1982.

- A partially mummified skeleton of Anomalopteryx didiformis from Southland – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 17: 399–408 – R. M. Forrest – 1987.

- Mummified moa remains from Mt Owen, northwest Nelson - Notornis 36 (1): 36–38. - Trevor H. Worthy - 1989.

- On evidence for the survival of moa in European Fiordland – New Zealand Journal of Ecology 12 (Supplement): 39–44 – A. Anderson – 1989.

- Unique, dark olive-green moa eggshell from Redcliffe Hill, Rakaia Gorge, Canterbury - Notornis 39 (1): 63–65. - Beverley McCulloch - 1992.

- Quaternary fossil faunas from caves in the Punakaiki area, West Coast, South Island, New Zealand – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 23: 147–254 – T. H. Worthy & R. N. Holdaway – 1993.

- Quaternary fossil faunas from caves in Takaka Valley and on Takaka Hill, northwest Nelson, South Island, New Zealand – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 24 (3): 297–391 – T. H. Worthy & R. N. Holdaway – 1994.

- Quaternary fossil faunas from caves on Mt. Cookson, North Canterbury, South Island, New Zealand – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 25 (3): 333–370 – T. H. Worthy & R. N. Holdaway – 1995.

- Morphology, myology, collagen and DNA of a mummified moa, Megalapteryx didinus (Aves: Dinornithiformes) from New Zealand

- Tuhinga: Records of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa 4: 1–26 – P. Vickers-Rich, P. Trusler, M. J. Rowley, A. Cooper, G. K. Chambers, W. J. Bock, P. R. Millener, T. H. Worthy & J. C. Yaldwyn – 1995.

- A reappraisal of the late Quaternary fossil vertebrates of Pyramid Valley Swamp, North Canterbury – New Zealand Journal of Zoology 24: 69–121 – R. N. Holdaway & T. H. Worthy – 1997.

- Quaternary fossil faunas of Otago, South Island, New Zealand – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 28 (3): 421–521 – Trevor H. Worthy – 1998a.

- The Quaternary fossil avifauna of Southland, South Island, New Zealand – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 28 (4): 537–589 – Trevor H. Worthy – 1998b.

- A preliminary report on the nesting habits of moas in the East Coast of the North Island – Notornis 46: 457–460 – W. H. hartree – 1999.

- Rapid Extinction of the Moas (Aves: Dinornithiformes): Model, Test, and Implications – Science 287 (5461): 2250–2254 – R. N. Holdaway & C. Jacomb – 2000.

- reversed sexual size dimorphism in the extinct New Zealand moa Dinornis - Michael Bruce, Trevor H. Worthy, Tom Ford, Will Hoppitt, Eske Willerslev, Alexei Drummond & Alan Cooper - 2003.

- Nuclear DNA sequences detect species limits in ancient moa - L. Huynen, C. D. Millar, R. P. Scofield & D. M. Lambert - 2003.

- Plant remains in coprolites: diet of a subalpine moa (Dinornithiformes) from southern New Zealand. - Emu Austral Ornithology - Mark Horrocks, Donna D’Costa, Rod Wallace, Rhys Gardner & Renzo Kondo - 2004.

- Reconstructing the tempo and mode of evolution in an extinct clade of birds with ancient DNA: The giant moas of New Zealand - Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102 (23): 8257–8262 - Allan J. Baker, Leon J. Huynen, Oliver Haddrath, Craig D. Millar & David M. Lambert - 2005.

- Cortical growth marks reveal extended juvenile development in New Zealand moa – Nature 435 (7044): 940–943 – Samuel T. Turvey, Owen R. Green & Richard N. Holdaway – 2005.

- Rediscovery of the types of Dinornis curtus Owen and Palapteryx geranoides Owen, with a new synonymy (Aves: Dinornithiformes) - Tuhinga (16): 33–43 - Trevor H. Worthy - 2005.

- Moa gizzard content analyses: further information on the diet of Dinornis robustus and Emeus crassus, and the first evidence for the diet of Pachyornis elephantopus (Aves: Dinornithiformes) – Records of the Canterbury Museum 21: 27–39 – J. R. Wood – 2007.

- Eggshell characteristics of moa eggs (Aves: Dinornithiformes) – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 37 (4): 139–150 – B. J. Gill – 2007.

- A deposition mechanism for Holocene miring bone deposits, South Island, New Zealand – Journal of Taphonomy 6: 1–20 – J. R. Wood, T. H. Worthy, N. J. Rawlence, S. M. Jones & S. E. Read – 2008.

- Moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) nesting material from rockshelters in the semi-arid interior of South Island, New Zealand – Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 38 (3): 115–129 – J. R. Wood – 2008.

- The evolutionary history of the extinct ratite moa and New Zealand Neogene paleogeography - Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (49): 20646 - M. Bunce, T. H. Worthy, M. J. Phillips, R. N. Holdaway, E. Willerslev, J. Haile, B. Shapiro, R. P. Scofield, A. Drummond, P. J. J. Kamp & A. Cooper - 2009.

- Ancient DNA Reveals Extreme Egg Morphology and Nesting Behavior in New Zealand’s Extinct Moa – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (30): 16201 – Leon Huynen, Brian J. Gill, Craig D. Millar, David M. Lambert – 2010.

- Tinamous and Moa Flock Together: Mitochondrial Genome Sequence Analysis Reveals Independent Losses of Flight among Ratites – Systematic Biology 59 (1): 90–107 – Matthew J. Phillips, Gillian C. Gibb, Elizabeth A. Crimp & David Penny – 2010.

- Twenty-first century advances in knowledge of the biology of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes): A new morphological analysis and moa diagnoses revised - New Zealand Journal of Zoology 39 (2): 87 - T. H. Worthy & R. P. Scofield - 2012.